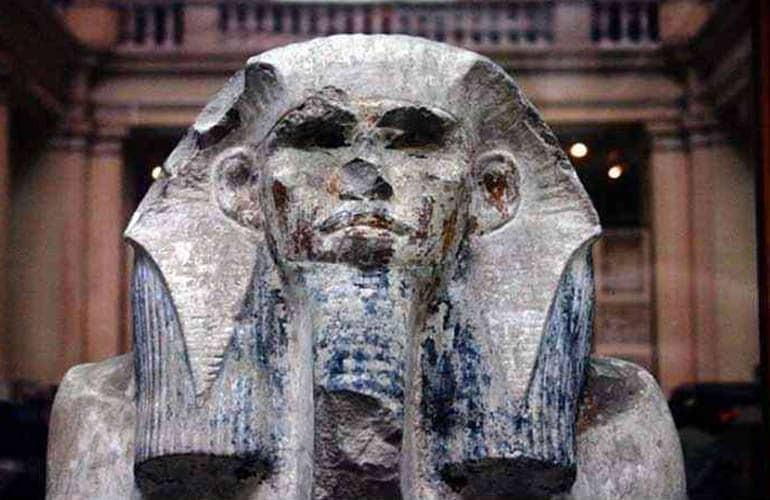

King Zoser’s Face: Third Dynasty’s Quiet Ruler

The painted limestone statue of Zoser, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, is the oldest known life-size Egyptian statue. The statue was found during the Antiquities Service’s excavations of 1924-1925. Today, at the site in Saqqara where it was found, a plaster copy of the statue stands in place of the original.

In contemporary inscriptions he is called Netjerikhet, meaning “divine in body.” Later sources, including a New Kingdom reference to his construction, help confirm that Netjerikhet and Djoser are the same person.

While Manetho names Necherophes and the Turin King List names Nebka as the first ruler of the Third Dynasty, many Egyptologists now believe that Zoser was the first king of this Dynasty, pointing out that the order in which some of Khufu’s predecessors are mentioned in the Westcar Papyrus suggests that Nebka should be placed between Zoser and Huni, not before Zoser. More significantly, the English Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson has shown that funerary seals found at the entrance to the tomb of Khasekhemwy at Abydos mention only Zoser and not Nebka. This supports the view that Zoser buried and directly succeeded Khasekhemwy rather than Nebka.

Family

Djoser is linked to Khasekhemwy, the last king of the Second Dynasty of Egypt, through his wife Queen Nimaethap (Nimaat-hap), via seals found in Khasekhemwy’s tomb and at Beit Khallaf. The Abydos seal names Nimaat-hap as the “mother of the king’s sons, Nimaat-hap.” In mastaba K1 at Beit Khallaf, the same person is mentioned as the “mother of the dual king.” The dating of other seals at the Beit Khallaf site places them in the reign of Zoser. This evidence suggests that Khasekhemwy is Zoser’s direct father or that Nimaat-hap had him through a previous husband. German Egyptologist Gunter Dreyer found Zoser’s sealings in Khasekhemwy’s tomb, further suggesting that Zoser was Khasekhemwy’s direct successor and that he finished the construction of the tomb.

His cult seems to have been still active in the later reign of Snefru.

Hetephernebti is identified as one of Zoser’s queens “on a series of boundary stelae from the Step Pyramid enclosure (now in several museums) and a relief fragment from a building at Hermopolis” now in the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

Inetkawes was his only daughter known by name. A third royal wife was also attested during Zoser’s reign, but her name was destroyed. Zoser’s relationship with his successor, Sekhemkhet, is unknown, and the date of his death is uncertain.

Reign

The lands of Upper and Lower Egypt were united into a single kingdom around 2686 BC. The period following the unification of the crowns was one of prosperity, marked by the beginning of the Third Dynasty and the Old Kingdom of Egypt. The exact identity of the founder of the dynasty is a matter of debate due to the fragmentary nature of records from the time. Djoser is one of the leading candidates for the founder of the Third Dynasty. Other candidates include Nebka and Sanakht. Possibly complicating matters further is that Nebka and Sanakht refer to the same person.

Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson believes that the weight of archaeological evidence favours Zoser (Netjerikhet) as Khasekhemwy’s successor and founder of the Third Dynasty. A seal from Khasekhemwy’s tomb at Abydos, combined with a seal from mastaba K1 at Beit Khallaf dating to Djoser’s reign, links the two pharaohs as father and son respectively. The Abydos seal names a ‘Nimaat-hap’ as the mother of Khasekhemwy’s sons, while the other seal at Beit Khallaf names the same person as the ‘mother of the dual king’. Further archaeological evidence linking the reigns of the two pharaohs is found at Shunet et-Zebib, suggesting that Zoser oversaw the burial of his predecessor. The stone ritual vessels found at the tomb sites (Khasekhemwy’s tomb at Abydos and Djoser’s tomb at Saqqara) of the two pharaohs also appear to have come from the same collection, as samples from both sites contain identical images of the god Min. This archaeological evidence is complemented by at least one historical source, the Saqqara king list, which names Zoser as Beby’s immediate successor, a misinterpretation of Khasekhemwy.

Length of reign

Manetho states that Zoser ruled Egypt for twenty-nine years, while the Turin King List states it was only nineteen years. Because of his numerous major building projects, particularly at Saqqara, some scholars argue that Zoser must have enjoyed a reign of nearly three decades. Based on Wilkinson’s analysis and reconstruction of the Royal Annals, Manetho’s figure appears to be more accurate. Wilkinson reconstructs the Annals as giving Zoser “28 full or partial years”, noting that the cattle counts recorded in the Palermo stone register V and Cairo Fragment 1, register V, for the beginning and end of Zoser’s reign, would likely indicate his reign years 1 to 5 and 19 to 28. The coronation year is preserved, followed by the year the twin pillars were received and the ropes for the Qau-Netjerw (“hills of the gods”) fortress were tightened. Unfortunately, almost all entries are illegible nowadays.

Period of reign

Various sources provide various dates for Zoser’s reign. Professor of Ancient Near Eastern history Marc van de Mieroop dates Zoser’s reign to between 2686 BC and 2648 BC. Authors Joann Fletcher and Michael Rice date his reign to between 2667 BC and 2648 BC, giving a regnal period of either partial or full 18 years. Rice further states that Nebkha was Zoser’s brother and predecessor. Writer Farid Atiya provides a regnal period similar to Fletcher and Rice’s, offset by a single year: 2668 BC to 2649 BC. This dating is supported by authors Rosalie and Charles Baker in Ancient Egypt: People of the Pyramids. Egyptologist Abeer El-Shahawy, in association with the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, places Zoser’s reign between 2687 BC and 2648 BC. and 2668 B.C. for 18 similar partial or complete years. Author Margaret Bunson places Zoser as the second ruler of the Third Dynasty and sets his reign from 2630 B.C. to 2611 B.C. for a partial or complete 19-year reign. In her chronology, Zoser is preceded by Nebka as the “Founder of the Third Dynasty,” reigning from 2649 B.C. to 2630 B.C. She, like Rice, makes Nebka Zoser’s brother.

Political activities

Zoser sent several military expeditions to the Sinai Peninsula, where the local inhabitants were subdued. He also sent expeditions to mine valuable minerals such as turquoise and copper. The Sinai was also of strategic importance as a buffer between the Nile Valley and Asia. This is known from inscriptions found in the desert there, which sometimes show the standard of Set alongside symbols of Horus, as had been more common under Khasekhemwy.

His most famous monument was his step pyramid, which involved the construction of several mastaba tombs one on top of the other. These forms eventually led to the standard pyramid tomb in the later Old Kingdom. Manetho, many centuries later, alludes to the architectural advances of this reign, mentioning that “Tosorthos” discovered the construction with dressed stone, as well as being remembered as the physician Aesculapius and for introducing some reforms in the writing system. Modern scholars think that Manetho originally attributed (or intended to attribute) these feats to Imuthes, who was later deified as Aesculapius by the Greeks and Romans and corresponded to Imhotep, the famous minister of Zoser who designed the construction of the step pyramid.

Some fragmentary reliefs found at Heliopolis and Gebelein mention Zoser’s name and suggest that he commissioned building projects in those cities. Furthermore, he may have set the southern boundary of his kingdom at the First Cataract. There is an inscription known as the Famine Stele, which claims to date from Zoser’s reign but was probably created during the Ptolemaic dynasty. This inscription relates how Zoser rebuilt the temple of Khnum on the island of Elephantine at the First Cataract, thus ending a seven-year famine in Egypt. Some consider this ancient inscription to have been a legend at the time it was written. Nonetheless, it shows that the Egyptians still remembered Zoser more than two millennia after his reign.

Although he appears to have begun an unfinished tomb at Abydos (Upper Egypt), Djoser was eventually buried in his famous pyramid at Saqqara in Lower Egypt. Since Khasekhemwy, a pharaoh of the Second Dynasty, was the last pharaoh to be buried at Abydos, some Egyptologists infer that the move to a more northern capital was completed during Djoser’s time.

Zoser and Imhotep

One of King Zoser’s most famous contemporaries was his vizier (tjaty), “chief of the royal shipyard” and “overseer of all stonework,” Imhotep. Imhotep oversaw stone construction projects such as the tombs of King Zoser and King Sekhemkhet. Imhotep may have been mentioned in the also famous Westcar Papyrus, in a story called “Khufu and the Magicians.” But because the papyrus was badly damaged early on, Imhotep’s name has been lost today. A papyrus from the ancient Egyptian temple of Tebtunis, dating to the 2nd century AD, preserves a long story in demotic writing about Zoser and Imhotep. By Zoser’s time, Imhotep was of such importance and fame that he was honored to be mentioned on King Zoser’s statues in his necropolis at Saqqara.

Grave

Zoser was buried in his famous step pyramid at Saqqara. This pyramid was initially built as an almost square mastaba. Still, five more mastabas were stacked on top of each other, each smaller than the last, until the monument became the first step pyramid in Egypt. The supervisor of the building’s constructions was the high priest Imhotep.

The pyramid

The step pyramid is made of limestone. It is huge and contains only a narrow corridor leading to the centre of the monument, ending in a rough chamber where the entrance to the tomb shaft was hidden. This inner construction was later filled with rubble, as it was no longer of any use. The pyramid once had a height of 62 metres and a base of ca. 125 x 109 metres. It was covered with finely polished white limestone.