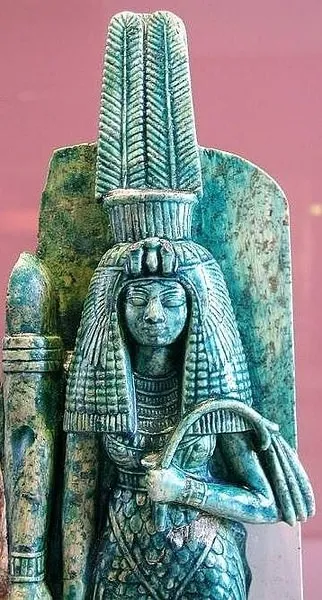

Queen Tiye: One of the Most Influential Women of Ancient Egypt Tiye was queen, wife of Amenhotep III, Origins Unlike all her predecessors, Tiye was not of royal lineage

Queen Tiye Amulet 83d40m (Public Domain)

Tiye (also known as Tiy, 1398-1338 BCE) was a queen of Egypt of the 18th dynasty, wife of the pharaoh Amenhotep III, mother of Akhenaten, and grandmother of both Tutankhamun and Ankhsenamun. She exerted an enormous influence at the courts of both her husband and son and is known to have communicated directly with rulers of foreign nations.

The Amarna letters also show that she was highly regarded by these rulers, especially during the reign of her son. Although she believed in the traditional polytheistic religion of Egypt, she supported Akhenaten’s monotheistic reforms, most likely because she recognized them as important political stratagems to increase the power of the throne at the expense of the priesthood of Amun.

She died in her early sixties and was buried in the Valley of the Kings. Her mummy has positively been identified as that known as the ‘Elder Lady’, and a lock of her hair, possibly a keepsake of the young king’s, was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Early Life & Marriage

According to some scholars (Margaret Bunson, among them), Tiye’s father was Yuya, a provincial priest from Akhmin, and her mother was Tjuya, a servant of the queen mother, Mutemwiya. Other sources, however, claim Yuya was Master of the Horse of the royal court and Tjuya a priestess. Tiye grew up in the royal palace but was not a royal herself. She would have been a part of the court life if her mother had been the queen’s servant but it seems more likely that both her parents enjoyed a more elevated status.

She had one brother, Amen, who later took over his father’s position and eventually became high priest of the cult of Akhmin, and she may have had another brother, Ay, who would later rule Egypt (though this is disputed). Her parents’ names, some claim, are not Egyptian, and it has been suggested that they were Nubian. Scholars who have noted Tiye’s unusual role in the affairs of state point to the Nubian custom of female rulers. The Candaces of Nubia were all strong female rulers, and so some scholars speculate that perhaps Tiye felt free to wield power in the same way as a male ruler because of her upbringing and heritage.

Tiye ruled with the same authority as a man and exercised her power in equal measure with the great kings of the ancient world.

This theory is disputed, however, as it has been pointed out that women in ancient Egypt had more rights and were held in higher regard than in most other ancient cultures and, therefore, there is no need to seek a reason in neighboring Nubia for Tiye’s behavior.

The counter-argument, however, is that this latter objection does not account for the Nubian-sounding names of Tiye’s parents. The Egyptologist Zahi Hawass claims that the names are not Nubian and that “some scholars have speculated that Yuya and Tjuya were of foreign birth, but there is no good evidence to substantiate this theory” (28). He also contradicts Bunson by claiming that Tiye’s parents were associated with the clergy from the Egyptian region of Akhmin, serving the gods Amun, Hathor, and Min; Yuya was Master of the Horse and Tjuya was not a servant of the royal house but a priestess of considerable power.

If Hawass is correct, this would explain how Queen Tiye came to wield as much power as she did — far more than any other queen of Egypt before her (as Hatshepsut was pharaoh, not queen, she cannot be considered in this equation).The historian Margaret Bunson notes that, “Tiye probably married Amenhotep while he was a prince. She is believed to have been only 11 or 12 at the time” (265). When Amenhotep III came to the throne, Tiye ascended with him.

Queen Tiye

From the beginning of her husband’s reign, Tiye was a significant force at court. Bunson writes that she was “intelligent and diligent, the first queen of Egypt to have her name on official acts, even on the announcement of the king’s marriage to a foreign princess” (265). Hawass agrees, stating, “Tiye is featured prominently on her husband’s monuments, and seems to have borne more real power than the queens who came before her. Her name is even written in a cartouche, like that of the king” (28). Amenhotep III’s reign was luxurious, and Egypt was the most powerful and richest nation in the region, if not the world, and so the king was free to expend this wealth in building a grand palace for his queen at Malkata, across the river from Thebes and the old palace of his father.

Queen Tiye Bust

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta (CC BY-SA)

Tiye and her husband lived at Malkata where she gave birth to six children: two sons, Thutmosis, Amenhotep IV; and four daughters, Sitamen, Henuttaneb, Isis, Nebetah, and Baketaten. Thutmosis died early in life, and Amenhotep IV (later known as Akhenaten) was pronounced heir to the throne. Images from the time show Tiye with her family enjoying domestic life, but she was equally involved in affairs of state.

Besides the customary titles for a queen, like Hereditary Princess, Lady of the Two Lands, King’s Wife, or Great King’s Wife, Tiye was also known as Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mistress of the Two Lands. The royal couple presented a united front in dealing with domestic and foreign policies, and the reign of Amenhotep III is considered a high point in Egyptian history. Hawass writes:

Putting her non-royal origins beside her evident power, scholars have long assumed that the marriage between Amenhotep III and Tiye was a love match. However, scholars now think it possible that her parents, Yuya and Tjuya, actually held a good deal of influence in the central administration under Thutmosis IV, and may even have served as regents during the minority of the young king. The marriage may then have been a successful bid for power by an ambitious family. They were granted the unusual privilege of burial in the Valley of the Kings, where their partially plundered but still rich tomb was discovered in 1905. (28)

There is no doubt, however, that the king and queen loved each other and enjoyed each other’s company. They are depicted as constant companions and, as Hawass notes, “The palace at Malkata had an enormous artificial lake attached to it. Amenhotep III and Tiye took pleasure cruises on this lake in their Aten bark” (31) and also strolled in the gardens. Every inscription, statue, or letter presents the couple as equal partners in both domestic and public life.

Tiye’s importance is evident in that she is depicted in statuary as the same height as her husband. Previously, in dyad statuary representing pharaoh and his queen, the king was considerably taller to symbolize his greater power and prestige. From inscriptions and the letters found at Amarna, it is clear that Tiye was in every way the equal of her husband and presided at festivals, met with foreign dignitaries, and directed both domestic and foreign policies.

Bunson writes that “Tiye was mentioned by several kings of other lands in their correspondence, having been made known to them in her official dealings” (265). Amenhotep III’s great contribution to Egyptian culture was the peace and prosperity which enabled him to erect his great monuments, temples, public parks, and palaces. Bunson notes, “While Amenhotep busied himself with his own affairs, Queen Tiye worked tirelessly with officials and scribes overseeing the administrative aspects of the empire. She was devoid of personal ambition and served Egypt well during her tenure” (18). The royal couple ruled Egypt successfully for 38 years until Amenhotep III’s death in 1353 BCE when he was 54 and Tiye was 48 years old.

The King’s Mother

Tiye assumed the title of King’s Mother upon the ascent to the throne of her son Amenhotep IV. Initially, he ruled from Malkata and continued his father’s policies but, in the fifth year of his reign, he abolished the old religion of Egypt, closed the temples, and proclaimed a new order based on the worship of the one true god Aten. He changed his name to Akhenaten and built a new city, with an even grander palace, on virgin land in the middle of Egypt, which he called Akhetaten (horizon of Aten).

Love History?

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Even though there is no indication that Tiye had ever entertained anything like monotheistic leanings, she seems to have supported her son’s radical departure from the religious policies of the past. The priests of Amun had gradually been growing in wealth and power throughout the 18th dynasty until, by Amenhotep III’s reign, their influence was on par with the royal house. Whatever Tiye may have thought of her son’s monotheism privately, she would have approved of a measure to increase the power of the throne at the expense of the clergy.

Funeral Mask of Queen Tiye

Keith Schengili-Roberts (CC BY-SA)

During Akhenaten’s reign, Tiye is depicted in the role of a grandmother sitting with the royal children of her son and his wife, Nefertiti, but she continued to play an important role in the political life of Egypt. The king of Mitanni, Tushratta, carried on a correspondence directly with Tiye and even mentioned matters having nothing to do with state issues such as the pleasant times they had passed together in visits. Akhenaten is routinely depicted with his mother in domestic scenes or official visits to Akhetaten, and he was clearly very fond of her. Even her servants held her in high regard. She is depicted with her family enjoying a banquet on the wall of the tomb of her steward Huya, where she is bathed in the light of the god Aten and is surrounded by her grandchildren.

Bunson writes that depictions of Tiye at this time “show a forceful woman with a sharp chin, deep-set eyes, and a firm mouth” (265), and she continues to be depicted as a figure of prominence and royal stature. Her example is thought to have served as a model for her daughter-in-law, as Nefertiti enjoyed much the same status as Tiye, served the court in the same capacity, and, most importantly, took care of the affairs of state when her husband was otherwise occupied or distracted from his duties.

Tiye’s Death & Legacy

It is not known when Tiye died, but it was most probably around the twelfth year of Akhenaten’s reign in the year 1338 BCE. The painting and inscription on Huya’s tomb is the last known mention made of her and is dated to that year. Her death is seen by some as coinciding with Akhenaten’s seeming loss of interest in foreign affairs, and perhaps his grief over the loss of his mother influenced his withdrawal. It has also been suggested, however, that he may have had no interest all along and simply left affairs of state to his mother and Nefertiti.

Either way, his reign suffers a marked decline after Tiye’s death, and he largely neglected foreign policy, preferring to remain in his palace at Akhetaten and attend to his new religion. This preoccupation with Aten led to a decrease in Egypt’s prestige and the loss of a number of territories long held by the crown, notably Byblos, as well as the rise in strength of the Hittites to the north since there was no longer a significant Egyptian foreign policy to check their expansion.

These circumstances have led scholars to speculate that, had she lived longer or perhaps exerted more direct influence on her son’s religious interest, the Amarna Period would have been remembered more favorably by future generations of Egyptians. As it came to be, however, Akhenaten would come to be considered `the heretic king’ and his reign wiped from memory.

Following Akhenaten’s death, his son Tutankhamun took the throne, repealed his father’s religious reforms, and re-instituted the old religion of Egypt. Akhenaten’s monotheism was so hated by the people of Egypt that measures were taken by his successors, Tutankhamun first and then Ay following him, to bury the legacy of the `heretic king’, put his reign behind them, and build Egypt back to its former height.

The last king of the 18th dynasty, Horemheb, took these measures further and, claiming the gods had chosen him to restore Egypt to its former glory, tried to erase Akhenaten from history. He ordered the temples to Aten, the stele, and even the city of Akhetaten destroyed. The only way scholars in the modern day know anything about the Amarna Period is because Horemheb used the ruins from Akhenaten’s reign as fill in constructing new temples to the ancient gods of Egypt and, from these ruins, the reign of the heretic king has been pieced together. It is for this reason, also, that Tiye’s death date, and even her initial place of burial, is a matter of debate.

Tiye appears to have first been buried in the tomb of Akhenaten and then re-buried in the tomb of her husband Amenhotep III. There is no clear agreement on this, however, because the argument for burial in Amenhotep III’s tomb is based on the discovery of her Shabti dolls there but nothing else. Further, her actual mummy was discovered (by the archaeologist Victor Loret in 1898 CE) in the tomb of Amenhotep II. The claim that she was first buried in her son’s tomb is supported by inscriptions but, as these writings are not clear and often incomplete, they are open to interpretation.

Her mummy was first identified only as “The Elder Lady” and it was only later, when more information came to light on the reign of Akhenaten, that she was positively identified by name. At this time it became clear that, centuries before the reign of Cleopatra, well known from Greek and Roman accounts, there existed a queen of Egypt who ruled with the same authority as a man and exercised her power in equal measure with the great kings of the ancient world.

This article has been reviewed by our editorial team before publication to ensure accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards in accordance with our editorial policy.