Guatemala’s Mayan Figure: A 1,500-Year-Old Helmeted Find

A charming scene of 23 ceramic figurines, arranged by mourners in a circular configuration inside a royal tomb chamber, tells a story about the ritual life of the ancient Maya. This scene includes a deceased king accompanied by his spirit animal companion, a magical deer wearing an oval pendant with a capital “T” motif engraved on it. For the ancient Mayans, this was the Ik’ symbol, which represented breath, wind and life.

This marks the deer as the guide of the deceased king on his journey through the underworld until his resurrection.

They are joined in a circle by other former members of Mayan royalty: the warrior queen proudly holding a shield; a living king who wears the rich, multi-layered textiles befitting his position; the heir to the throne presenting an enema syringe to administer hallucinogens essential to the ceremony; and dancers, scribes and ladies who perform at this sacred event. These actors are joined by other more formidable beings, who have access to the supernatural and can conjure deeper powers: a shaman whose face is contorted in an ecstatic howl, dwarves with removable helmets ready to engage in ritual boxing to attract healing rains. life, and a dwarf in a deer helmet holding a snail trumpet that will be played not only for music, but also to open the portal to the underworld.

The LACMA exhibition, Ancient Bodies: Archaeological Perspectives on Mesoamerican Figures which I curated, features this Mayan resurrection ritual scene. It was revealed to us through an archaeological excavation conducted by me, Varinia Matute, and a stellar team of trained specialists and excavators from both the US and Guatemala. It was 2006 and we were working on a monumental pyramid in the ancient city of El Perú-Waka’, located in the Laguna del Tigre National Park in Petén, Guatemala, within the Mayan Biosphere Reserve.

I am still a member of the El Perú-Waka’ Regional Archaeological Project (PAW), and I am honored to be part of a team that continues to conduct various investigations at the site. Waka’ is constantly threatened by illicit activities such as looting and park invaders who set fires to burn the forest to graze livestock or establish illegal settlements within the park boundaries. These activities also endanger the natural resources within the park, including the extraordinary animals that were sacred to the ancient Mayans, such as scarlet macaws and stealthy jaguars, which often fall prey to poachers. Our project, as well as other archaeological projects in Laguna del Tigre and adjacent parks, provide a stable presence to help deter illegal activity. When we can, we collaborate with the Wildlife Conservation Society, a vital organization actively trying to preserve this area of the Petén.

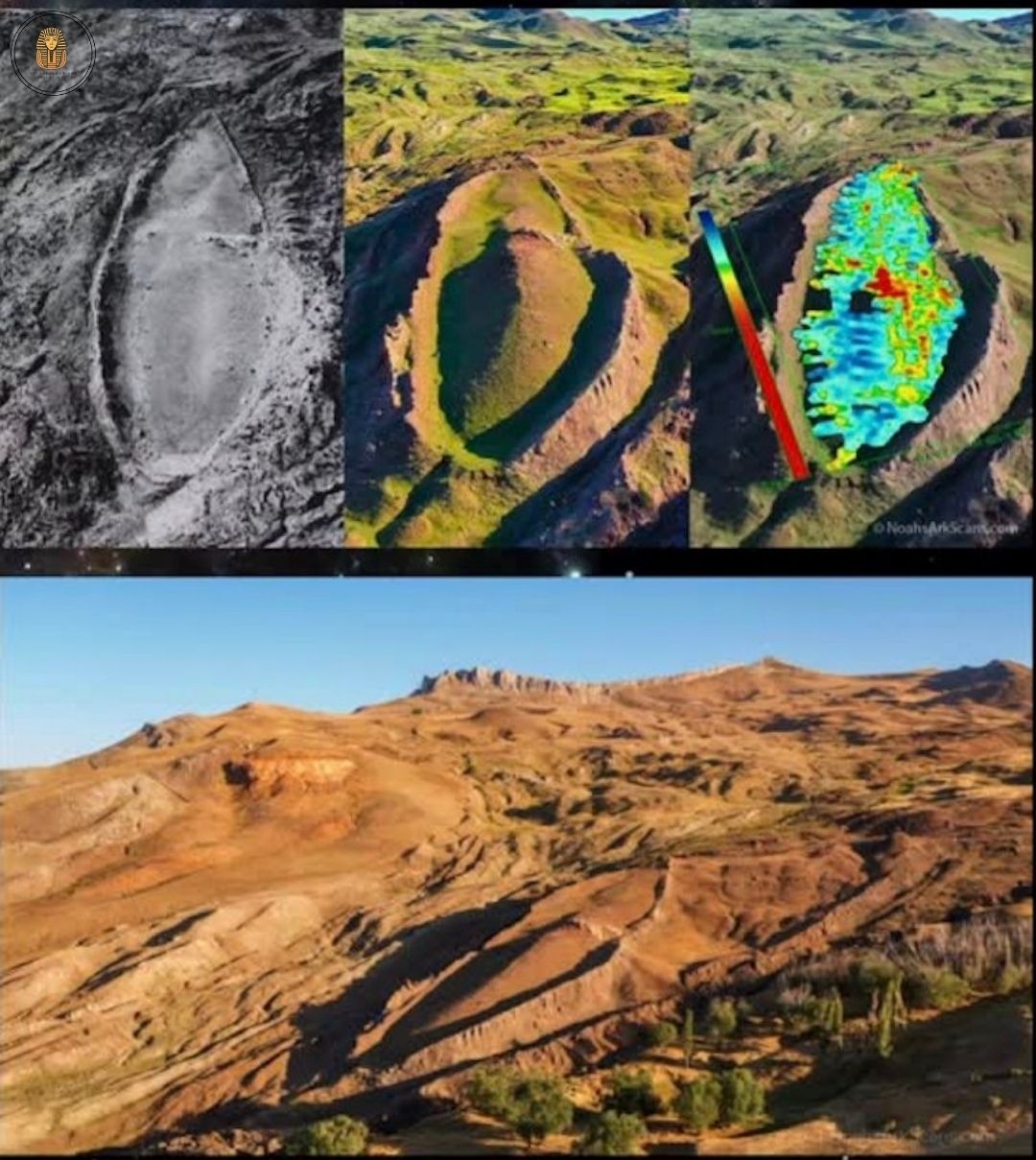

View of the monumental funerary pyramid called Str. O14-04, location of Burial 39 in El Perú-Waka’, Petén, Guatemala, pH๏τo © Patrick Aventurier

The figurines were arranged as described above by mourners participating in their own ritual. They were burying a deceased ruler of Waka’ in a domed masonry burial chamber built within the imposing pyramid, known prosaically as Structure O14-04. This was the 39th burial excavated at Waka’, hence the official record as Burial 39. The ruler was placed in majesty on the funerary bench, also made of carved stone, along with the objects that make up the mortuary complex.

We excavated 32 ceramic vessels, greenstone earflaps, a jadeite mosaic mask, and many other artifacts typical of Classic period tombs. These elite contexts help us understand the “one percent” of ancient Mayan society, but archaeologists are interested in learning about all levels of society and aspects of the past. As such, PAW is made up of a full team of researchers investigating everything from ancient soils to settlement areas and palatial architecture. In Burial 39, along with the aforementioned artifacts favored by the passage of time, the tomb would also have flourished with contents that archaeologists in this subtropical region do not normally have the good fortune to record. These include food offered to sustain the deceased on their journey and items made from animal skins, paper, wood, gourds, feathers, and the rich textiles that we know served as tribute in ancient Mayan royal courts. In burial 39, we were lucky to find remains of cloth, not from the ruler’s clothing, but from the material used to wrap the body before burial. It took me three days of excavating skeletal elements with these bits of “stuff” attached to them to realize what it was; Even as an experienced archaeologist, I had never seen cloth on a dig!

Thanks to the techniques we used during the excavation of Burial 39, we were able to preserve this remarkable ancient arrangement that provides three-dimensionality to the scenes we see in the polychrome vases of the Classic period (see the publication Unframed by Associate Curator Megan O’Neil on Chocolate to see several examples of glasses with various scenes). As an archaeologist, it is a special privilege to work on the cities, buildings and tombs that were sacred spaces to the ancient Maya, and we consider them as such today. Our efforts to record these contexts bring a richer history to the Mayan past, and I am delighted to have had the opportunity to collaborate with the National Museum of Archeology and Ethnology in Guatemala City to bring the Mayan Resurrection Ritual Scene to LACMA.

A stunning Mayan ritual scene has been uncovered in Guatemala’s El Perú-Waka’, showcasing 23 ceramic figurines buried with a ruler over 1,000 years ago. The figurines depict dancers, shamans, royalty, and a spirit guide—a deer with a sacred “Ik'” symbol—representing the king’s journey through the underworld. This intricate burial, along with rare cloth fragments and jade artifacts, sheds light on Mayan beliefs about life, death, and resurrection.