Akhenaten: The Forgotten Pioneer of Atenism and Monotheism

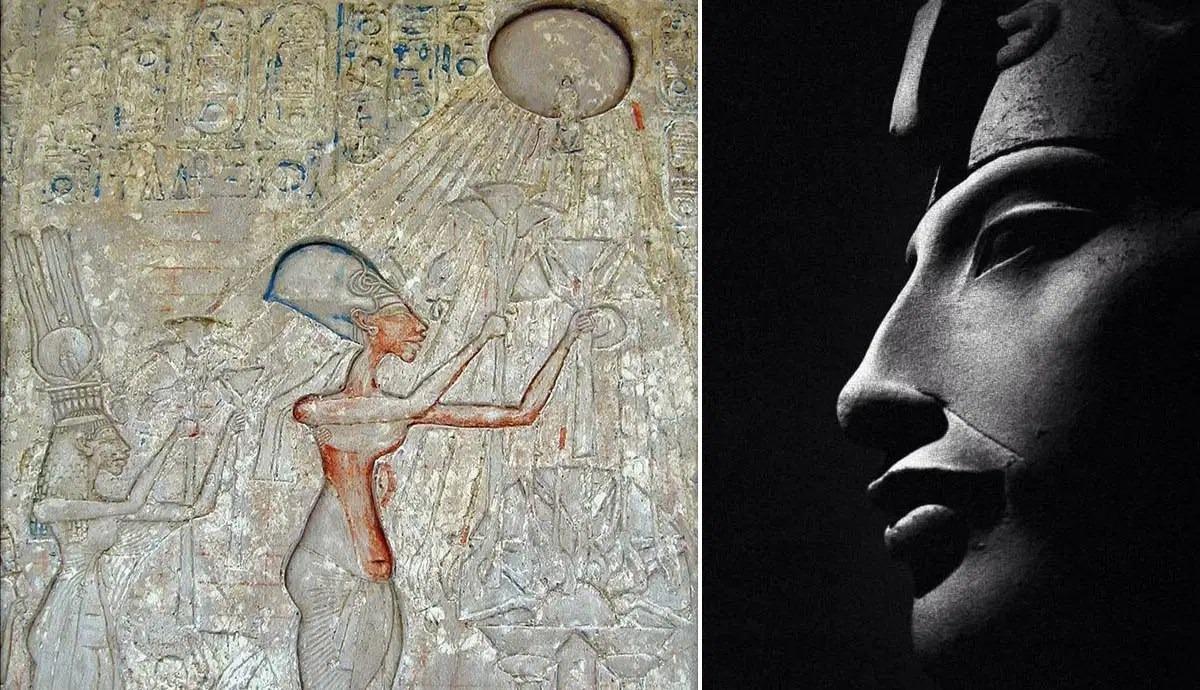

The image of the actor and writer Amin al-Jamal, the closest to King Akhenaten, one of the rulers of the 18th dynasty who ruled Egypt for 17 years and died perhaps in 1336 BC or 1334 BC. Early inscriptions depict a furnace with the sun, compared to the stars. Later, the official language avoided calling Aten a god, and the sun god gave him a higher status than that of a simple god.

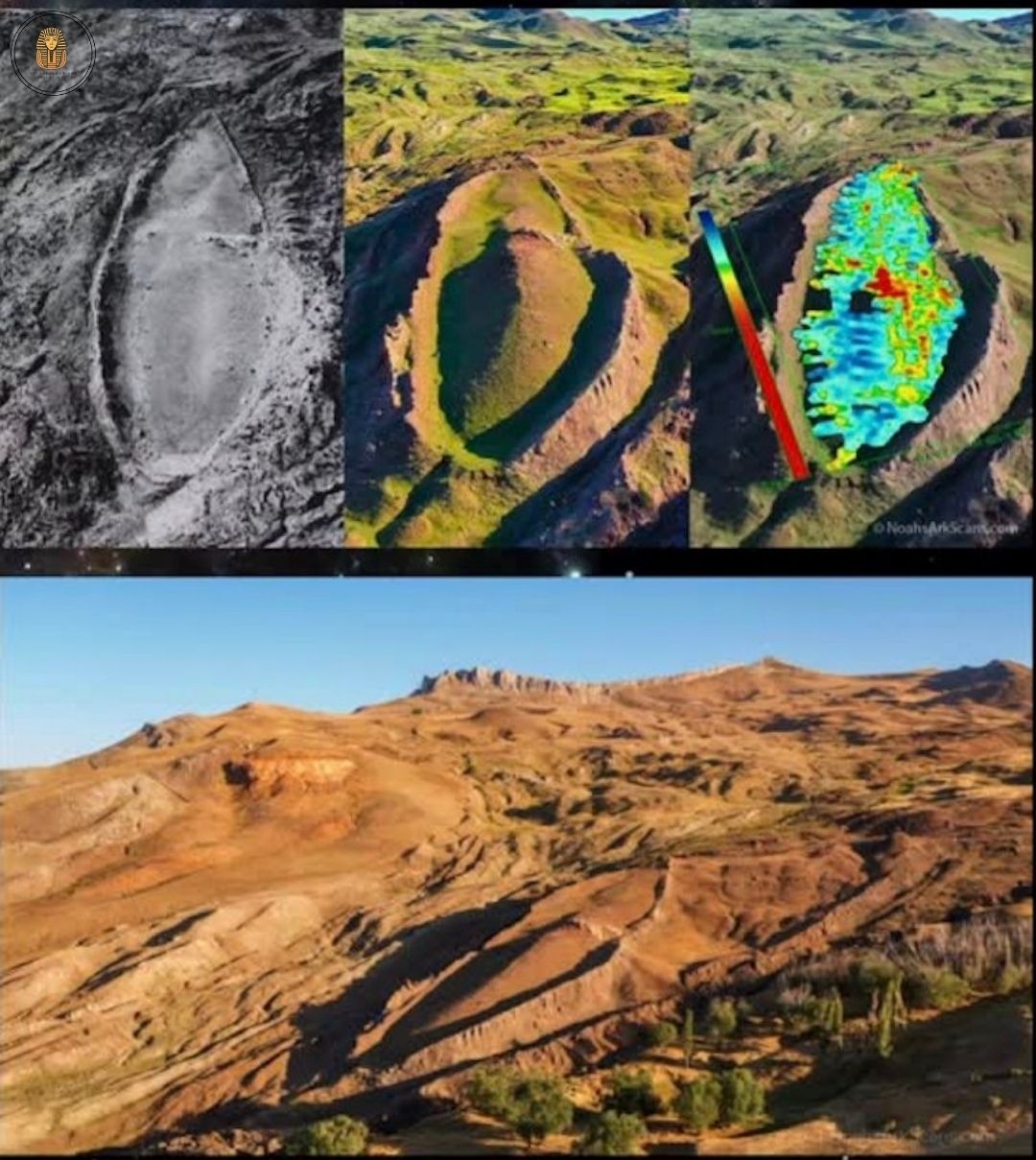

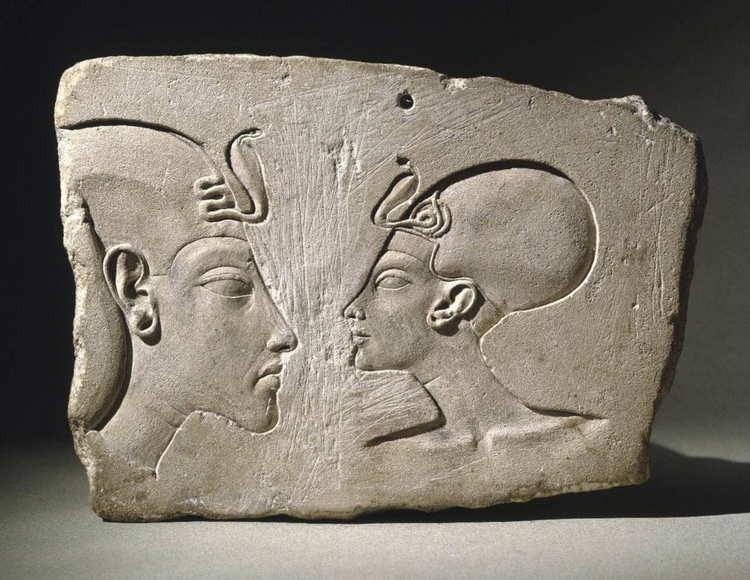

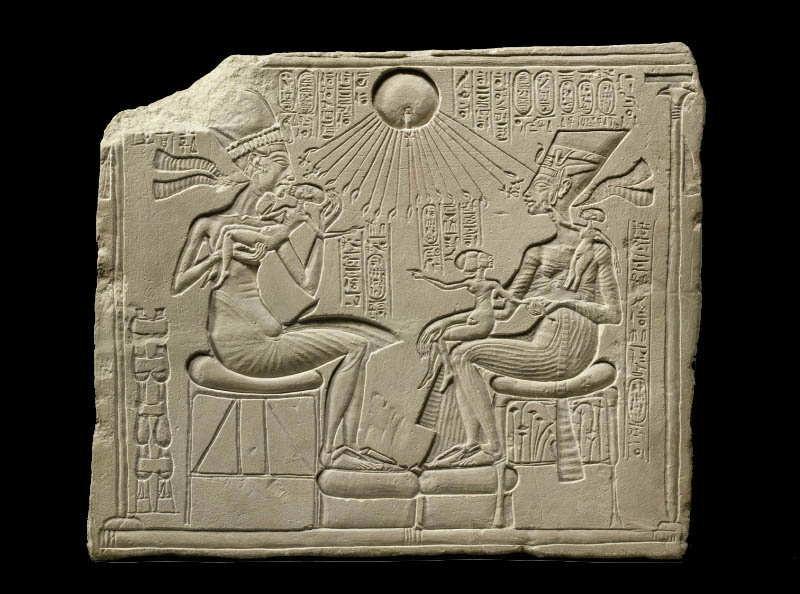

Relief of Akhenaten, Nefertiti and two daughters worshipping Aten, 1372-1350 BC.

Under the rule of King Akhenaten, Egypt came to worship a single sun god, Aten, thus forming Atenism. Akhenaten’s institution of monotheism throughout Africa from the 14th century BCE, though brief and quickly revoked, bears striking similarities to all three Abrahamic religions today. Because his successors destroyed tablets, temples, and other monuments dedicated to him after the overthrow of his empire, little is known about the methods by which Akhenaten established a new hierarchy within Egypt.

Akhenaten’s greatest achievements

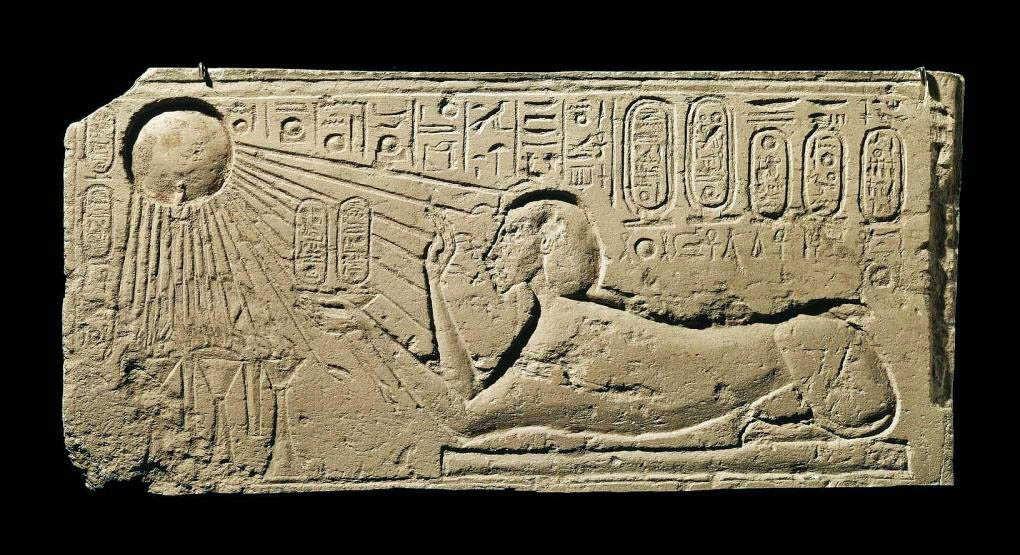

Relief of Akhenaten as a sphinx, Egyptian, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, 1349–1336 BC, MFA, Boston

Historians believe that Akhenaten’s greatest achievement—introducing the god Aten to worshipers across his nation—was designed to consolidate power around himself, rather than simply around a single god. As many prophets in the Abrahamic tradition have done, Akhenaten introduced the idea of his god’s preeminence to the Egyptian population by crafting a narrative and claiming to be the mouthpiece of his god. Through several carefully crafted steps, including changing his own name (originally Amenhotep) to reflect that of the Aten, Akhenaten manipulated the course of history and created a new precedent, if only for a couple of decades.

The rise of the cult of Aten

The Wilbour Plate , limestone plate, c. 1352-1336 BC, Brooklyn Museum

The first step of Akhenaten’s plan to reorient Egypt’s religious life began shortly after his rise to power in 1349 BC, when Akhenaten instituted a cult of the Aten and changed his name to reflect this god (Akhenaten means “One is effective for the Aten”).

The second step was carried out when he sent his workers to remove all images and names of previously worshipped gods. This might remind modern-day followers of the Abrahamic religions of the commandment “not to make for yourself another carved image.” The king commissioned new monuments depicting himself and his family conversing with the Aten.

Consolidating public dedication to Aten

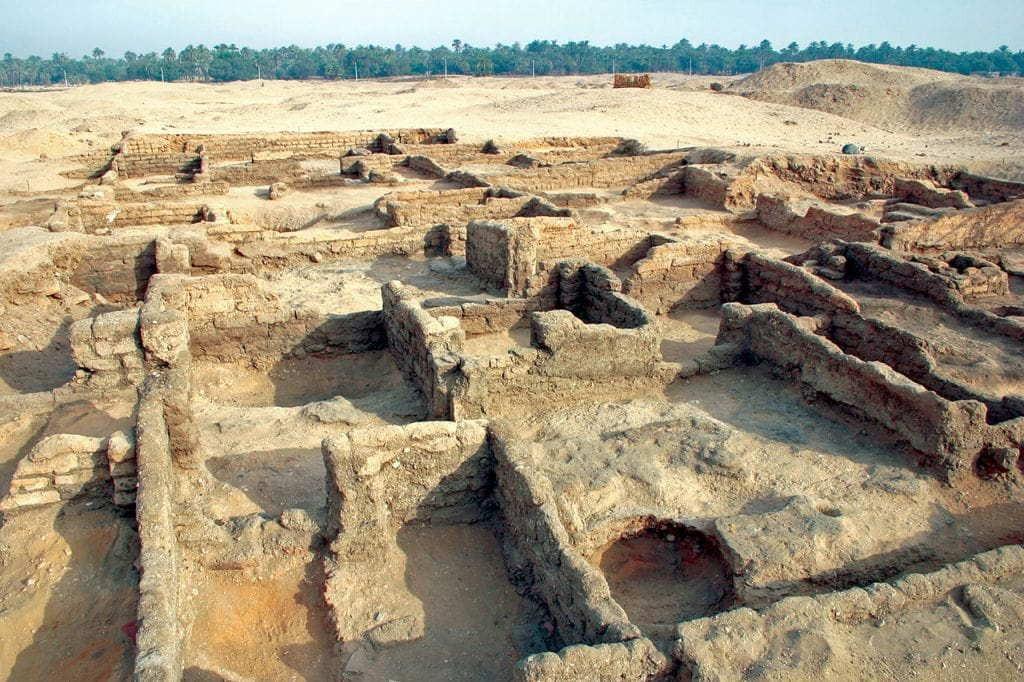

Tell-el Amarna excavation site, Oxford Handbooks Online, “Palaces Built to Impress”, Brown University

Receive the latest articles in your inbox

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter

Step Three was in full swing by the fifth year of his reign, during which Akhenaten dedicated an entire new city along the Nile River to Atenism, erecting dozens of temples in his name, filling them with images of prosperous harvests to inspire worshipers. This marked the beginning of the artistic Amarna Period, named after Tell-el-Amarna, the new capital established by Akhenaten. The capital was called “Akhetaten,” meaning “Horizon of the Aten.”

The fourth step changed the way the royal family was depicted in art of the time. Carvings of the royal family gave them elongated, androgynous bodies that were much larger than other humans shown in art of the time. This step brought Akhenaten’s family closer to the Aten in the minds of his people, distancing them from the proletariat by giving him and his relatives an otherworldly appearance.

Akhenaten exalts the cult of Aton by eliminating all others

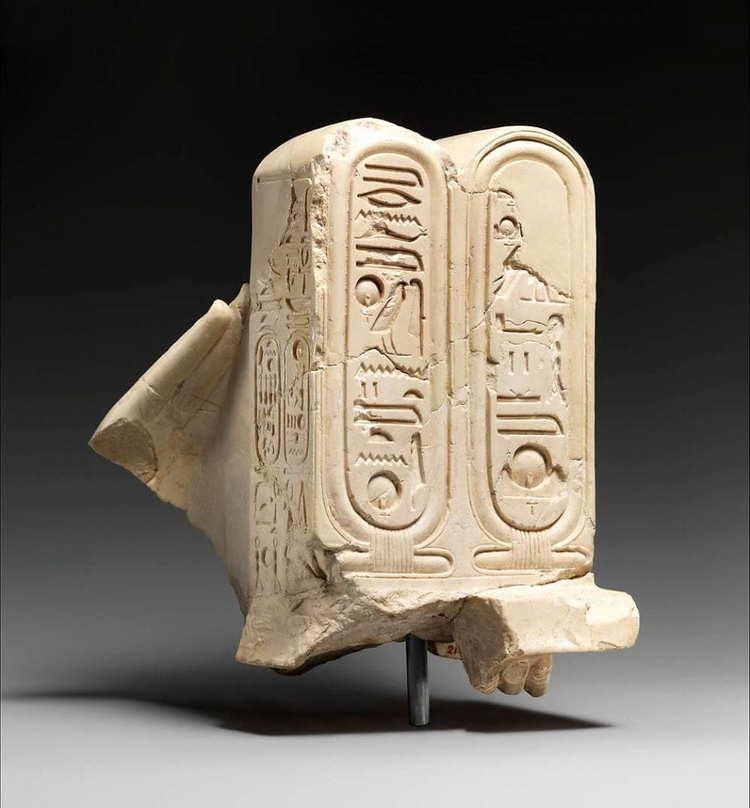

Hands offering Aten cartouches , ca. 1352-1336 BC, found in the Sanctuary of the Great Temple of the Aten, Met Museum

Step Five was fully realized in the early 1340s BC, by which time Akhenaten had eliminated all other priesthoods within Egypt and had become the only connection between the Egyptians and the realm of the gods. All Atenist worship, all sacrifices, and therefore all benefits were suddenly diverted to Akhenaten and his family, eliminating the status of all other priests and demoting all previous pharaohs to a position far lower than that of the current king.

Destruction of Atenism

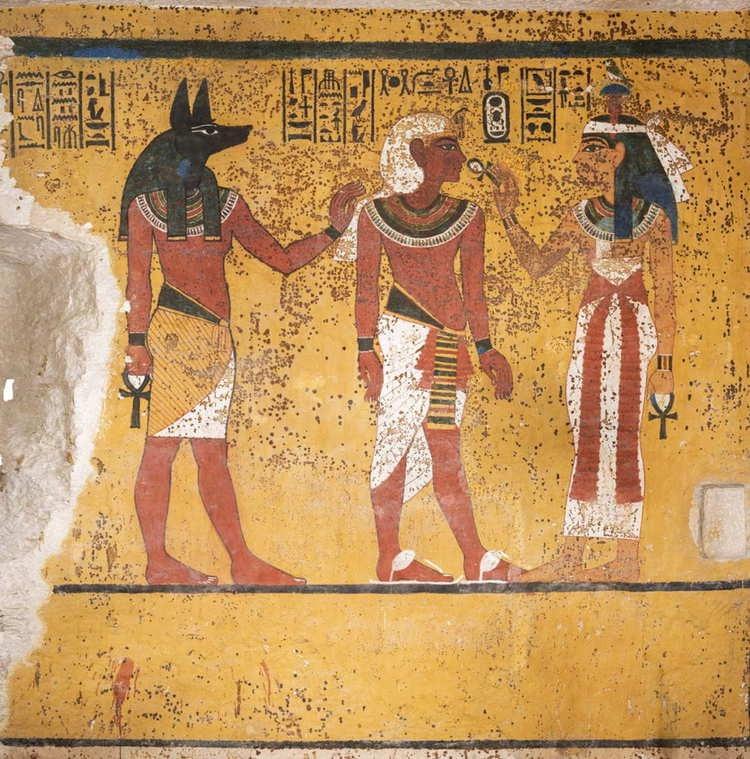

South wall in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, from “See Stunning Photos of King Tut’s Tomb After Major Restoration,” History.com

After his death, Akhenaten was succeeded by the boy king Tutankhamun, whose name has become better known in the current vernacular than that of his predecessor. Tutankhamun, who ascended the throne at age nine in 1324 BC, was dominated by regents and hardly ruled as a monarch. During the later years of Akhenaten’s reign and during that of Tutankhamun, a sect of Egyptians who had remained faithful to the cults of prominent gods before the Aten was imposed on them grew in influence.

Akhenaten, Nefertiri and their three daughters under the Aten, House Altar, Neues Museum, Berlin

These followers eventually quashed Akhenaten’s cult of the Aten and reinstated the polytheism of decades earlier, denigrating the sun god and his king into a mere footnote in Egyptian history until thousands of years later when he would become of interest to historical scholars. The above photo was taken from the south wall of King Tut’s tomb, which is covered with a wall painting of Tutankhamun standing with the gods Anubis and Hathor, demonstrating the removal of the Aten as Egypt’s sole and most important god.

Similarities between Atenism and the Abrahamic religions upon which 19th-century scholars relied

“God the Father” in Christianity and Atenism

God the Father on a throne, with the Virgin Mary and Jesus, Westphalia, Germany, late 15th century , via Biblical Studies

One of the most interesting commonalities between the religion of Aten and the religion of Christianity is that Akhenaten referred to himself as a son of Aten, giving himself the most special relationship a king could have with the gods. This father-son paradigm is echoed in Christianity, where Jesus is the son of “God the Father.” Indeed, just as Akhenaten proclaimed himself the sole king of Egypt and the son of Egypt’s sole god, Jesus is described in 1 Timothy 6:15 of the Christian New Testament as “the blessed and only Sovereign, the King of kings and Lord of lords.”

Destruction of temples

Destruction of the pagan idols from seven scenes from the legend of St. Stephen, Martino di Bartolomeo, 14th century, Städel Museum.

Akhenaten also set about destroying temples dedicated to other Egyptian gods, underscoring the preeminence of the Aten. Similarly, each of the Abrahamic religions has emphasized the importance of placing their God above all others and removing idols and altars to other gods. The Muslim faith proclaims, “God does not forgive idolatry, but He forgives minor offenses to whom He wills. Anyone who sets up idols beside God has committed a heinous crime” (4:48). 72:18 adds that “the places of worship belong to God; call upon none but God.” The Jewish faith echoes this sentiment in the book of Leviticus, where it is written, “Do not turn to false gods” (Leviticus 19:4). In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, the book of 1 Corinthians reestablishes this idea, with the command: “Therefore, my beloved, flee from idolatry” (1 Corinthians 10:14).

The gap in history and the unexplainable similarities

Reconstructed sarcophagus of Akhenaten , discovered in pieces in the Royal Tomb at Tell el-Amarna, Cairo Museum, via Wikimedia

Despite the many connections we can now draw between Atenism and these three religions, Akhenaten’s influence was largely forgotten in Egypt for thousands of years after his death. The pharaoh’s contributions were reintegrated into culture and religious thinking when 19th-century European archaeologists and amateur detectives began to plunder Egyptian relics. It is therefore fascinating to examine the similarities between Atenism, the first monotheistic religion, and the three Abrahamic religions, knowing that the founders of Judaism, Christianity and Islam had no access to this period of Egyptian history.

Napoleon Bonaparte marks the beginning of a renewed European obsession with Egypt

Photo of the Luxor Fountain and Obelisk, taken from Luxor and placed in the Place de la Concorde, Paris, by King Louis Philippe on October 25, 1836.

During Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a number of tombs and relics were raided by the French, resulting in a scientific analysis of their contents and an anthropological interest in the cultures connected with them. These “discoveries” made by the French in Egypt led to an obsession with Egyptian culture, art, architecture, history and politics throughout Europe, referred to as “Egyptomania”. Egyptomania was the trend responsible for bringing the story of Akhenaten and much of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty back into the cultural zeitgeist of the age, stimulating a number of comparisons between the beliefs of Victorian English Christians and Atenism, as well as new ideas across Europe about how Egypt and the three Abrahamic religions might relate to each other.

The enduring legacy of Egyptomania

The Death of Cleopatra , ‘The Death Knock’, Reginald Arthur, 1892, Christie’s

Egyptomania ignited a new interest in Egyptian history outside its classical confines (rooted primarily in the decades before the Common Era), which had been explored in literature, theater, and painting long before Napoleon’s campaigns. Although it was during the 19th century that Egyptomania was most fervent, the obsession has continued throughout Western history to the present day, marked by numerous exhibitions, publications, and films praising it. The 1994–95 exhibition “Egyptomania: Egypt in Western Art” marked the period 1730–1930 as the two-century period in which Egyptomania was prevalent in Europe and North America. The exhibition traveled from Paris to Canada and ended in Vienna, ironically where Sigmund Freud, the noted psychotherapist who also shared a love of Egyptian culture and history, established his psychiatry practice in 1886.

Sigmund Freud changes the conversation

Sigmund Freud’s desk , with part of his vast art collection, The Independent

Sigmund Freud’s Moses and Monotheism, written in 1939, just before the author’s death and after many years of developing his own collection of artifacts from Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and more, marked something of a culmination of Europe’s obsession with Egypt, most of which was, oddly, a very poorly received book at the time. The book outlines an alternative narrative to the story of Moses recorded in the Torah and the Christian Bible, claiming that Moses was not born to a Hebrew woman who put him in a basket in the river to later be found and adopted by an Egyptian woman; but rather that he was born an Egyptian. Freud set the time of the Exodus (the book in the Torah and Christian Old Testament in which Moses frees the Israelites from Egypt) slightly after the rule of Akhenaten, claiming that Moses was a follower of the Pharaoh’s religion who was uneasy about the return of Egyptian religious culture to polytheism.

Only fifty-two years earlier, Europeans had discovered Tel-El-Amarna and evidence of the cult of the Aten, leaving many analyses of this period still incomplete. Because of the controversial details Freud created about the subsequent murder of Moses by the Israelites, the book was initially dismissed, even though his understanding of Akhenaten would later be adopted as the prevailing assumption among historians. Some of today’s researchers and scholars have gone even further, with Egyptian author Ahmed Osman even going so far as to claim that Moses and Akhenaten were one and the same figure in his book Moses and Akhenaten: The Secret History of Egypt at the Time of the Exodus , which was published in 2002.

Regardless, Abrahamic religious scholars and historians will likely be referring to Akhenaten and the birth of monotheism for quite some time.