Ensuring Eternal Rest: Impaling the Heart of the Vampiric Skeleton to Prevent Its Return from the Dead

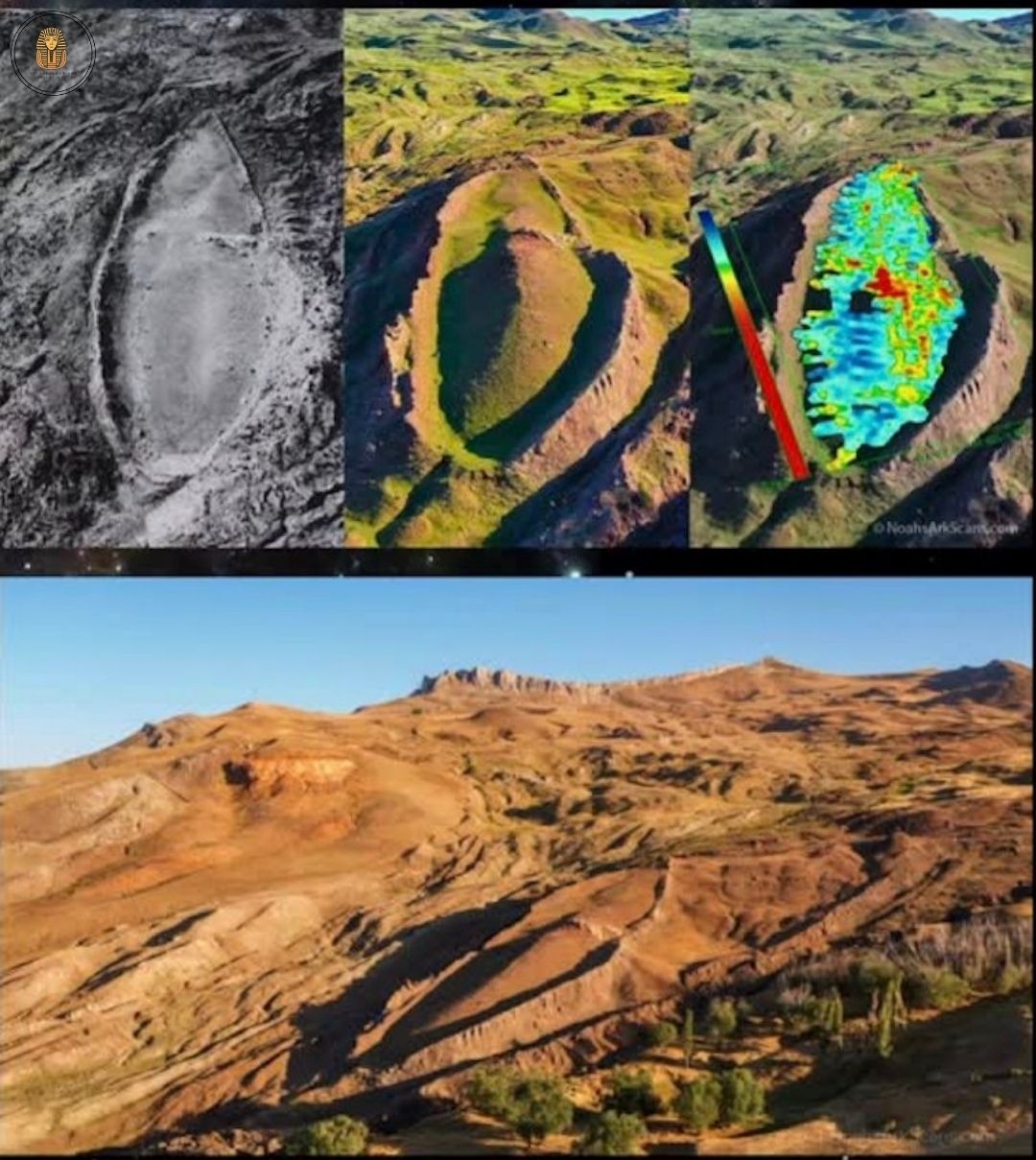

The ancient skeleton, identified as a 35- to 40-year-old man, is only the second skeleton with a pickaxe driven into its heart in this way, following one found last year in the southern town of Sozopol.

The man, considered a vampire for his medico-legal reasons, is believed to have been nailed to his grave with a metal stake, possibly to prevent him from rising from the grave and terrorising locals, he was found last year in the southern coastal town of Sozopol.

The discovery was made at the Perperikon excavation site in the east of the country during an excavation led by the chief archaeologist of the Bulgarian-German Project Nikolas Ovcharov.

Last year, a group led by Ovcharov unearthed another human skull about 700 years old with a wooden stick stuck in its skull at a church in the village of Sozopol.

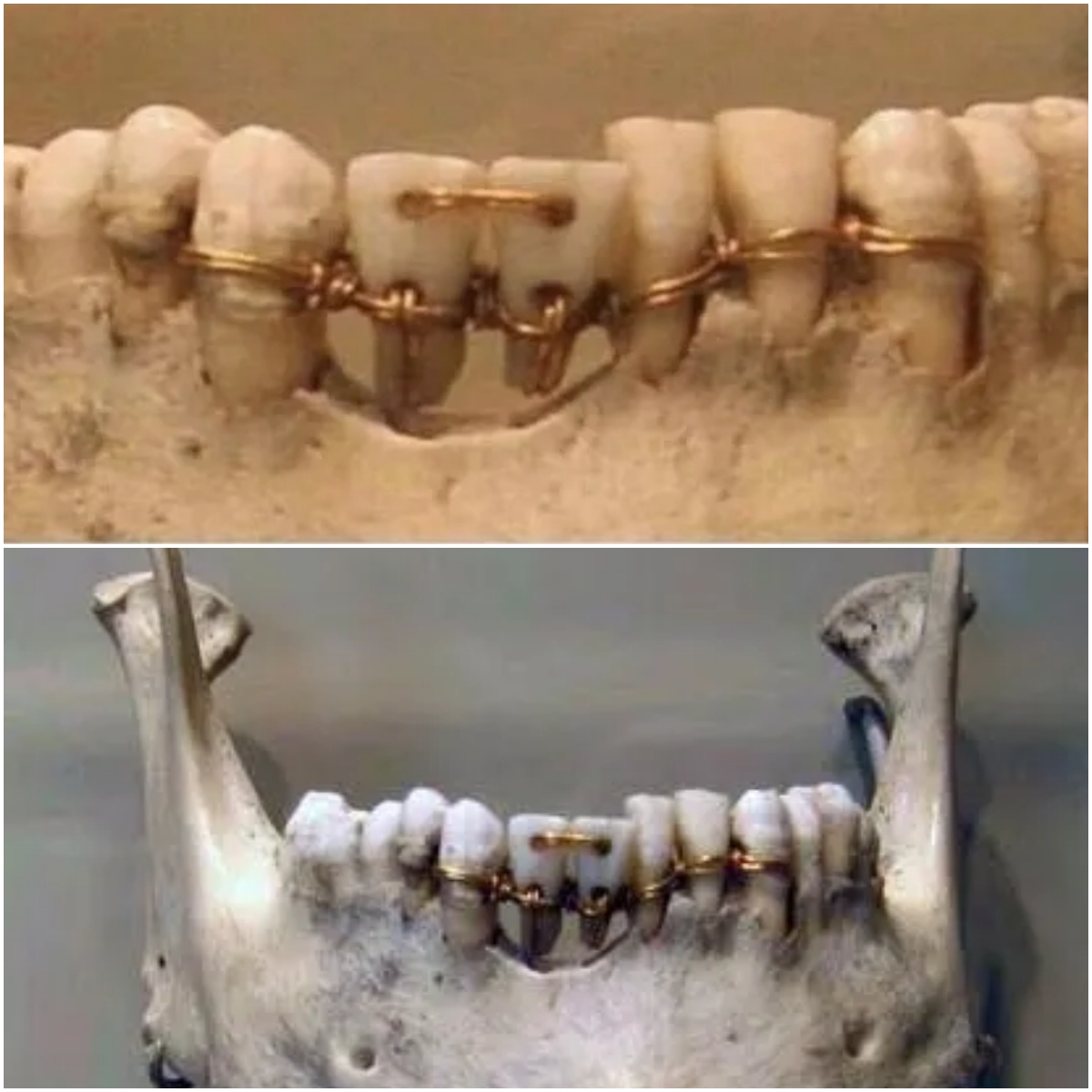

The skeleton, commonly known as the “Sozopol vampire,” was pierced through the chest with a wooden stick and its teeth were removed before being laid to rest.

Ovcharov has described the latest find as the “twin of the Sozopol vampire” and said it could shed light on how vampires benefited communities in medieval times based on Christian beliefs in the Middle Ages.

The body was dated to the 13th and 14th centuries.

In other cases, Professor Ovcharov said he had found skeletons nailed to the ground with steel stakes driven into the limbs, but this was only the second case where a stake was used in the heart.

“It [sticks] weighs almost 2 pounds (0.9kg) and is stuck into the body up to shoulder height,” he said.

“You can clearly see how the column has literally come out.”

This is the latest in a succession of finds in western and central Europe that have shed light on how people dealt with the threat of vampires.

According to Professor Belief, people who were considered evil during their lifetime could become vampires after death unless they were stabbed in the chest with a stick of oak or hawthorn wood before burial.

These “vampires” were intellectuals, aristocrats, aristocrats and clerics.

“The thing is that there were no women among them. They were witches,” said Bugaria’s natural history museum chief, Bozhidar Dimitrov.

The emergence of plagues that swept through Europe between 1300 and 1700 helped fuel the belief in vampires.

Disgusting mass gravediggers would follow a blow from some sort of gas-locked boots, with hair still growing, and blood seeping from their mouths. The shrouds used to cover the faces of the dead were torn by batiriá in the month, revealing the faces of the dead, remnants of lasso and vampires known as “shroud-eaters”.

According to medieval medical and religious texts, the “dead” were nailed to the ground to spread plague in order to suck the life out of their bodies until they were discovered by the rebirth of the remnants in order to return to the graves before their corpses decomposed.

“In my opinion, it is not about criminals or bad people,” Professor Ovcharov said.

The author argues that these are superstitions that prevent the soul of the deceased from being taken over by evil forces in the days following death.

More than 100 exhumed bodies were nailed to prevent them from turning into vampires in the country over the years.