Egypt’s Intact Tomb: A Pharaoh’s Final Rest

An unknown setting, the discovery of treasures rivals the discovery of the famous King Tutankhamun. This is the story of the Egyptian pharaohs and the reign of tennis.

Tutankhamun’s ankle is one of the most fascinating discoveries of all time, but it was not an intact discovery. It had been looted twice in antiquity, and Howard Carter estimated that a considerable amount of jewelry had been stolen. Over the three millennia, about 300 Egyptian tombs were looted by robbers, including Tutankhamun’s. But in 1939, Pierre Montet made one of the most important discoveries in archaeological history, the Tombs of Tanis. He found a neoclassical corner, including three intact tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs with their gold and silver treasures. This is the story of the glorious treasures of ancient Egypt.

Why this fascination with gold? At the dawn of ancient Egyptian civilization, people were trying to make sense of the world around them. They visualized it as beginning as an ocean of darkness and chaos. But then, out of the water emerged islands, the sun, the gods, and on the fertile land grew green vegetation. At dusk, they instinctively looked out into the darkness and chaos, and saw the stars, the moon, and on the surface of the earth, lush growth. Every day, the sun shone light on the world. Every year, the Nile fertilized the land. So they sensed a divine harmony in the world around them. And the balance of this fine web of life was the sun.

In the desert, one could find rocks as golden in color as the glow of the sun. They could be melted and shaped without fading, so they looked eternal. The ancient golden sun of Ra was described as having “his bones of gold, his flesh of silver, and his hair of lapis lazuli.” To the ancient Egyptians, the golden glow was made of the same substance as the sun, gold.

Gold, A Substance of Immortality

This is the legend of the bizarrely abandoned and yet another misunderstood ancient civilization of Egypt. It is not a civilization with a morbid fascination with death, but the opposite, life, for eternity. Since the sun is reborn every morning, the Egyptian Kings were built in the West. The goal was to join the sun on its nightly journey, and like it, be revived every morning.

This is how the pyramids express perpetuity. Originally covered with smooth stone and with a gold and silver lid, they shone like rays of sunlight. They also symbolized the eternal origin of vegetation, the radiance of the plant of life. The Egyptian pharaohs built impressive tombs with the aim of resurrecting themselves, by joining this eternal cycle of life.

And the Kings had one of their architects properly committed to Egyptian culture who also hoped to live eternally. Therefore, he took his job as a pyramid builder as a religious service and kept golden amulets on the king’s body for his eternal protection. Since the Pharaoh was considered divine in his time, he had the same needs as in the afterlife. So he carried out his wealth and precious objects to the tomb.

So how much would have accumulated over three millennia, if each king had accumulated wealth in his time? Can we even begin to imagine the treasury they wrote off?

The tomb of a minor king, Tutankhamun, contained more than 5,000 objects while the smallest royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. What would have become of the treasure of the greatest Egyptian pharaohs such as Ramses II?

First of all, what happened to the pyramids? In total, ancient Egypt built over 120 pyramids, including smaller ones made for queens and princes. Naturally, they had all been stripped of their mummies and treasures, the only thing left being some tombstone sarcophagus. Not a sack of gold, lapis or rubies to decorate. The last pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty, the helmet of Seneferu, the bracelet of Unas…

Fortunately, several royal treasures survived to give us a glimpse of what the last treasures might have looked like. They were recovered by thieves or archaeologists. And sometimes by accident, as when railroad workers stumbled upon a trove of treasures. The archaeologist suspected that it had already been looted two millennia ago. Among the treasures was a pair of gold and lapis lazuli necklaces bearing the name of Ramses II. We don’t know if he wore them, but it offers a glimpse into the last contents of his tomb.

In 1920 an archaeologist discovered a gold and lapis lazuli cobra in a pyramid. It had been left behind by thieves while they were taking the necklace. Imagine what the rest of it looked like, one needs to see the gold mask of Tutankhamun.

And as impressive as its treasures were, Tut’s tomb was not intact – it had been visited by robbers, twice. No intact royal tomb had been found in ancient Egypt, until Piye’s discovery at Tanis.

The glory capable of capturing the interest of Egyptian history was closed with the death of Ramesses XI. He carried a celebrated name, but none of the powers or achievements. Egypt entered one of its chaotic eras, and was divided in two. Desecrated, the Valley of the Kings was robbed of its treasures. Egyptian Pharaohs ruled from the Delta in the North. This is how the city of Tanis became the new capital.

But that was an era that was about to enter the ‘decline’ of Egyptian power. The city was built by the same hands that built the great Rameses as a suitable city. The high quality limestone made it very different that there was nothing to match Tutankhamun’s discovery.

The Valley of the Kings was not there, Tanis used to be the capital of Egypt. And after ten years of effort, in the spring of 1939, Pierre Montet found stone tombs. Then a small object, whose quality indicated that it was something special. This was not the floor of a temple, but the shelter of a crooked necropolis.

Thieves had been there in ancient times. Montet entered the hole they made to find a treasure of antiquities. But it was the time of a pharaoh, Osorkon II. Then, another sarcophagus was found, also damaged by theft.

And then, a chamber with no sign of entry. Slipping into the small chamber, Montet saw “a silver-headed falcon copulating. It was seen intact. Through a slit in the side, gold leaves gleamed.” Next to the silver falcon, “two scarabs were found in a pile of gold leaves.” The history of Egyptian archaeology was about to be rewritten.

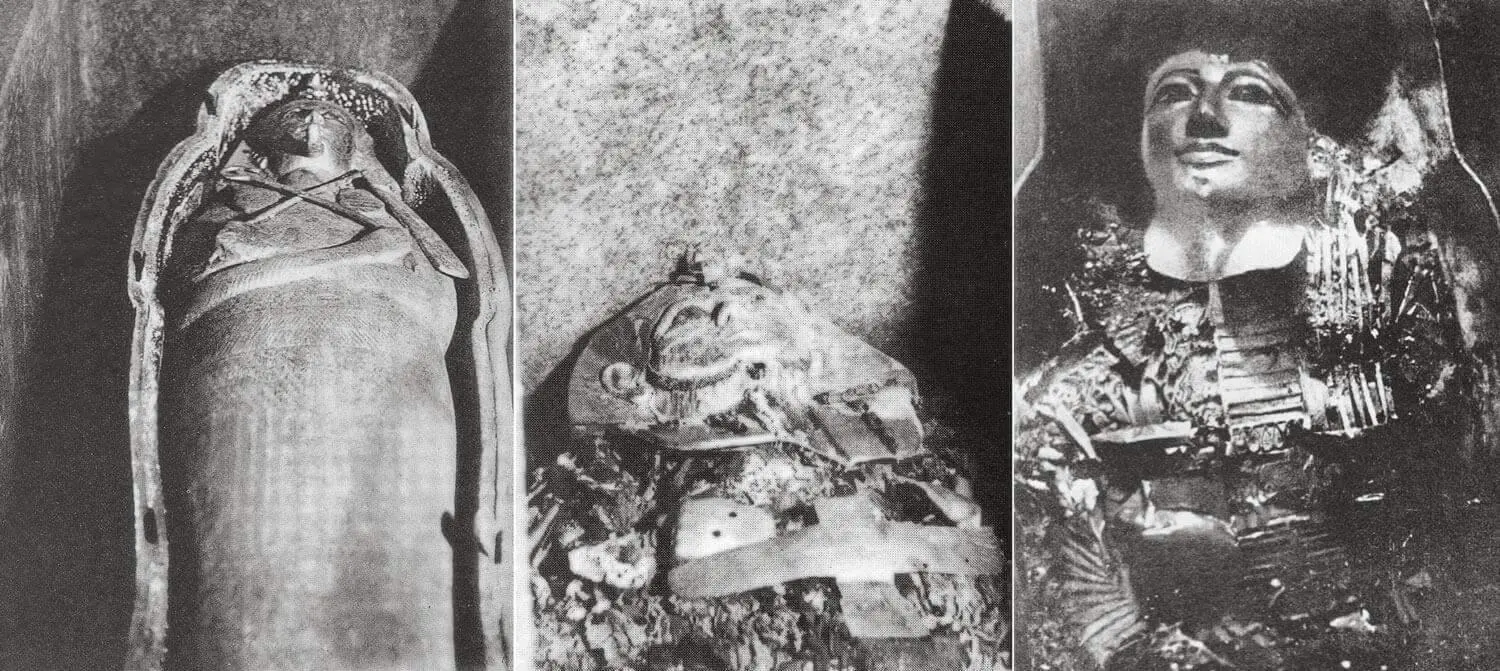

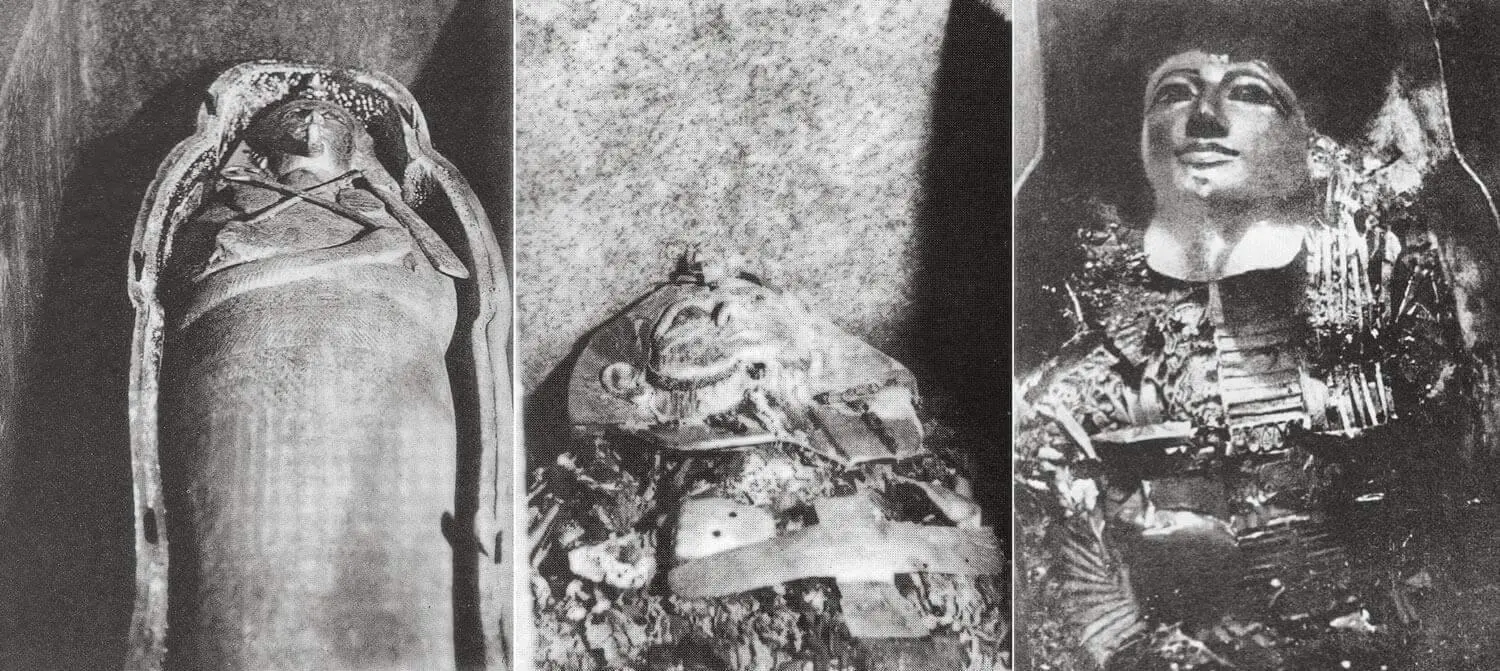

Montet had just found a royal necropolis, home to a dozen Egyptian tombs of kings and princes. The falcon-shaped coffin contained the mummy of Pharaoh Shoshenq II, a name that had until then been completely unknown. So the discovery of the first royal tomb ever found illustrated how much there was left to discover in ancient Egypt.

While the mummies had deteriorated badly, along with any texts on papyrus, gold maintained its reputation as an eternal substance. Everything made of wood had disappeared, but everything made of gold was intact.

Psusennes was buried inside a silver coffin. He was covered with a gold mask, six necklaces of gold or lapis lazuli, twenty-six bracelets and two pectorals. The largest necklace weighed 8 kg, made of thousands of individual gold pieces. It can be compared with the 10 kg (22 lb) used for Tutankhamun’s mask.

Each lapis lazuli necklace weighed 10 kg, the main gold necklace 8 kg (18 lb), a gold bracelet weighed 2 kg (4 lb). One wonders if Psusennes could even move if he wore all his jewellery.

There was also a fourth lavish coffin in the necropolis, a general named Unjebaud, whose tomb remained untouched. He too was in a silver coffin and his mummy was covered by a solid gold mask.

Under Pharaohs Shoshenq II and Amenemope, the Tanis hoard totaled nearly 600 objects. There were solid silver coffins, four gold masks, gold and silver vases, and an astonishing collection of jewelry. Shoshenq’s gold and lapis lazuli bracelets, as well as many of the other pieces, illustrated that the jewelry of a supposedly declining era was just as astonishing as Tutankhamun’s.

Montet contacted the Egyptian authorities as soon as the discovery was made, requesting security in every respect. He reflected: “I know from experience how much the discovery of gold unleashes a kind of gold fever. Like bees warned by a mysterious sense, people come from everywhere.” They did not need to travel far, as some of the mission workers themselves were caught in the act. So the treasure was quickly sent to the Cairo museum under army protection.

Then, during the war, knowing that the archaeologists would not be returning soon and that security was being reduced, the thieves returned. In 1943, the thieves not only visited the archaeologists’ house and warehouse. They entered the tomb of Psusennes and attacked two walls in search of a cache of jewels. No jewels were found, but many figurines were stolen.

The gold jewellery was in the Cairo museum’s safe. But “in the basement of the museum, authorities opened the safe where curators had secured Psusennes’ jewellery, concerned about the bombing. A vigorous investigation found most of what was stolen. Several elements of the necklaces and some small objects are missing.”

Montet highlighted the importance of the Tanis treasure as “the funerary monument of Psusennes, together with the two unified Egyptian ones, can be considered as one of the most significant collections that Antiquity left us. It would have been the first palace in Egypt if the tomb of Tutankhamun did not exist.”

And the timing of its discovery, in 1939 and 1940, did not help. Carter had been fortunate enough to study the burial mound in his time, and left behind photographs of the treasure trove to stimulate the imagination. But Montet had to work quickly. There was a war about to begin and gangs within the armed forces. Montet decided to take the treasure and hand it over to the authorities.

This explains why there are so few photos of the discovery. Still, it is difficult to understand why the Tanis treasure remains officially overlooked, as it is even displayed alongside the treasures of Tutankhamun.

Montet’s name should be remembered as much as Howard Carter’s. He discovered the only intact set of pharaohs from three millennia of civilization. They unearthed an intact royal necropolis, one of the most important finds in Egyptian archaeology.

But there are still aspects that challenge the Tanis hoard. For one, it is supposed to be from a declining era. Something confirmed by the short lifespan of the queens, can we even grasp the quantities of gold helped by the pharaohs?

Gold did not just cover the bodies of pharaohs inside the tombs. In some tombs, it covered walls, columns, doors, statues and furniture. Electrum, an alloy of about 80% gold and 20% silver, was used in the times of the powerful Pharaoh Ramses II and obelisks in the tomb.

What evidence do we have of the legendary gold of ancient Egypt? The pharaohs’ own words:

– Amenemhat I “built a palace adorned with gold, the roof of which was made of lapis lazuli.”

– In the palace of Ramses III “the ‘Great Seat’ is of gold, its pavement of silver, its doors of gold and black granite.” And the king himself had statues of gods made of “gold, silver, and every costly stone”.

– We also have the gold accounts of the pharaohs dating back to Amun. The greatest was Tuthmosis III who delivered 13.8 tons of gold and 18 tons of silver.

– However impressive these figures may be, they pale in comparison to Osorkon I, one of the Kings of Tanis. He is credited with donating 416 tons of precious metal to the temples. That is 25 tons of solid gold, 209 tons of electrum and 182 tons of silver. The list is incomplete and includes a sphinx weighing 4 tons of electrum.

During the Assyriology, Thébès Ashurbanipal’s engravings report stealing “silver, gold, and precious stones … two obelisks, made of shining electrum, whose weight was 2,500 talents.” The two electrum obelisks weighed 75 tons.

Another record of “silver and gold and costly works of gold and rare stones” was made by the Persians. Herodotus’ chronicles indicate that “not even the sand had been disturbed by votes, made of silver and gold and ivory, of such size and quantity.”

One problem addressed by historians is when these quantities conflict with each other. For example, the pair of electrum obelisks should have weighed, according to Ashurbanipal who stole them, 75 tons. But according to the records of the architect who probably built them, they weighed only 3.3 tons in total.

The other challenge is how to translate ancient weights into modern measurements. The Egyptian weight is the debe, corresponding to 91 grams (3.2 ounces). But according to some sources, it needs to be understood as half that for gold, or even 12 grams. This means that all the numbers given are probably lower. As Osorkon’s gold and silver weighed from 416 tons down to 208 tons, or even in its “low” equivalent of just 55 tons.

Are there other such astonishing amounts in history? A more recent example is the gold extracted from the New World between 1500 and 1660. The amount recorded in Spanish ports is 180 tons of gold and 16,600 tons of silver.

The other way to estimate Egypt’s gold is to try to establish how much has been mined. A recent study puts the total amount mined over three millennia of the Pharaonic era at 7 tons. And it meant melting down as much as 600,000 tons of rock to get that amount.

How to reconcile all these dazzling figures? Between what the pharaohs and foreign kings claimed, what outsiders saw, or were informed about; and what remained, that is the treasure of Tutankhamun and Tannis. In Egypt, as elsewhere, gold, silver, precious stones and metals were mined, melted, shaped and recast again into objects, jewels and statues. At one time, the gods, pharaohs and nobles. Then it was stolen, melted down, resold and mercilessly stripped. Some of the pharaohs’ gold jewels could be in Asyut (Iraq), Persia (Iran), Greece, or in Rome (Italy). Some of them could also have been sold today in the Cairo jewel market.

The ancient Egyptians saw gold as a reflection of their gods, as a precious metal that would help them live forever. As we have since learned, gold does not even come from the earth; it was common among the stars billions of years before. Perhaps they were not successful, after all, in believing that gold was the substance of immortality.