Rome’s Mystery Skull: Questions Linger On

A little-known period of Scandinavian prehistory has recently yielded some of the most extraordinary human remains ever found. Lying atop a dense layer of stone at the bottom of a small lake were pieces of ten humans who lived around 6000 BC. Even stranger than their location in a lake was what happened to them: most had shattered skulls, and two retained remnants of long wooden spikes that suggest their heads may have been dismembered and violently exposed.

In a paper in the journal Antiquity, Swedish archaeologists Sara Gummesson, Fredrik Hallgren, and Anna Kjellström describe a set of nine adult skeletons and one child skeleton found a few years earlier at the Kanaljorden site in east-central Sweden. A small lake at the site revealed a 12-meter by 14-meter area of compacted stone, along with human and animal bones placed on top of the purpose-made structure. Those bones have been carbon-dated to between 6000 and 5500 B.C.E., a time when there were at least two settlement areas on the nearby shores, with archaeological material indicating a hunting-gathering society.

The animal remains from the lake come from at least seven different species, including wild boar and brown bear. Cut marks on these fauna suggest that the animals were being handled and dismembered after death, potentially for a reason other than human consumption. The fact that none of the animal bones were burned provides further support for this hypothesis.

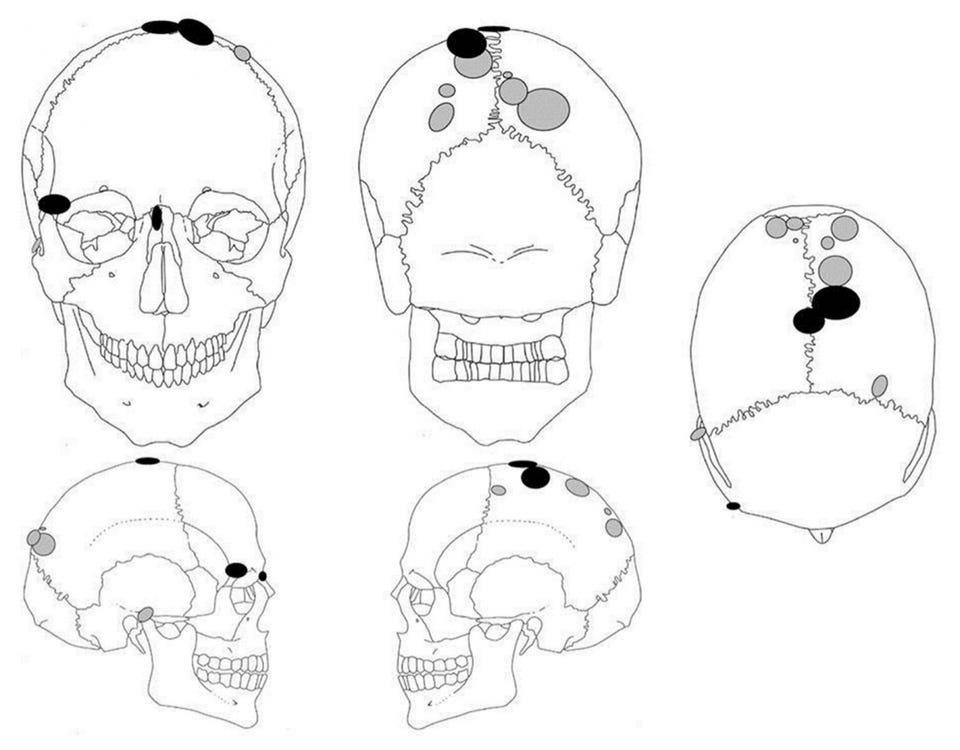

While using animal bones for ritual purposes may not seem too unusual, archaeologists discovered nine adult human skulls at the same site with startling wounds. Two were found to be female, four were male, and the rest were of indeterminate sex. The tenth individual was a full-term infant, but it is unclear whether it was stillborn or died shortly after birth.

The catalogue of injuries to the adult skulls includes blunt force trauma primarily to the top of the head and face, and both the women and the four men suffered these traumatic injuries. The women, however, “showed evidence of multiple instances of trauma to the back of the head,” Gummesson and colleagues write, “whereas the men exhibited a single traumatic event to the top of the head or face.” Three of the men also revealed acute trauma that occurred at the time of death.

Because the human remains were deposited in a lake with minimal water flow, they are remarkably well preserved, even eight millennia later. One skull contained traces of brain tissue, which archaeologists say means it was deposited shortly after death. The remarkable preservation conditions also allowed them to recover wooden objects, specifically some 400 intact and fragmented wooden stakes that suggest a fence or other partition.

However, two of these stakes were found inside skulls. In the image above, “the stake is intact, 25 mm wide and 0.47 m long, of which the last 0.2 m was embedded in the skull. The opposite end of the stake is pointed,” the archaeologists write. Another stake, albeit broken, was found partially lodged in a second skull. “In both cases, the stakes were inserted through the foramen magnum,” or the large hole in the skull through which the spinal cord passes, reaching the inner table of the skull. “These finds show that at least two of the skulls were mounted,” Gummesson and colleagues conclude.

The researchers note that the placement of these human heads in a man-made stone structure underwater is unique. But healed head injuries are not that rare: similar injuries are seen in other northern European populations from this period and have been attributed to accidents, interpersonal violence, forced abductions, spousal abuse, socially regulated violence, and warfare. Since “most blunt trauma at Kanaljorden was located above the hat brim line,” the archaeologists say this suggests “violence rather than accidental injury.”

The Kanaljorden people were hunter-gatherers, making it unlikely that this was a socially stratified society, where decapitated people were slaves or captives. Rather, the researchers note, “an alternative would be to view trauma as a result of intergroup violence – for example, raiding and warfare, both common phenomena among hunter-gatherers.”

More specifically, the different injury patterns in men and women may be related to their different roles and behaviors in combat, as Gummesson and colleagues note that “violence to the head is the most effective way to subdue an opponent or victim.” If these individuals were indeed victims of violence from outside their group, the fact that many of them have multiple healed wounds may speak to a life subjected to periodic acts of violence.

Neither the cause of death of these individuals nor the reason for the placement of two of them on stakes emerge from the archaeological investigation. However, given the location of the stones in the water and the bones above, the researchers conclude that “the deposition can be described as carefully planned and executed, from the construction of the stone fill underwater to the spatially separated depositions of cured human and animal remains.”

While ongoing research into this time and place will no doubt yield new information in the future, for now Gummesson and his colleagues can say that “the fact that most of the individuals showed healed wounds appears to be more than coincidental and implies that they were specifically chosen for inclusion in the declaration.” If additional human remains similar to those discovered at Kanaljorden are found, perhaps one day our questions about violence in Mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies will be answered.