Egypt’s Mummification Rituals: A Legacy Preserved

The ancient Egyptians believed that to enter the afterlife, the deceased’s body must be preserved through a process known as mummification. This sacred ritual, perfected over millennia, not only demonstrates the Egyptians’ advanced knowledge of anatomy and chemistry but also reflects their profound spiritual beliefs and cultural practices. This article explores the meticulous mummification techniques of ancient Egypt and examines their lasting impact on modern science and culture.

Why preserve the body?

The ancient Egyptians valued life and fervently believed in life after death, a belief that motivated their elaborate preparations for death. Contrary to what seems morbid, these preparations were based on a deep belief that life continued beyond death, which required the preservation of their physical bodies. The mummification process was intended to keep the body as alive as possible, something essential for the continuity of life in the afterlife.

The mummified body was believed to house the soul or spirit; The destruction of the body could cause the loss of the spirit and its inability to enter the afterlife. The preparation of the grave was a fundamental aspect of this belief, which began long before death and included the storage of items needed in the afterlife, such as furniture, clothing, food, and valuables.

Mummification techniques

The ancient Egyptian mummification process, as detailed in a 2011 study, was a sophisticated ritual that took 70 days to complete. This period was characterized by a combination of meticulous physical preservation techniques and spiritual practices carried out by priests who were also embalmers. The steps and variations of the mummification process reflect not only the technological expertise of the ancient Egyptians, but also the class distinctions that permeated their society.

Mummification techniques

The ancient Egyptian mummification process, as detailed in a 2011 study, was a sophisticated ritual that took 70 days to complete. This period was characterized by a combination of meticulous physical preservation techniques and spiritual practices carried out by priests who were also embalmers. The steps and variations of the mummification process reflect not only the technological expertise of the ancient Egyptians, but also the class distinctions that permeated their society.

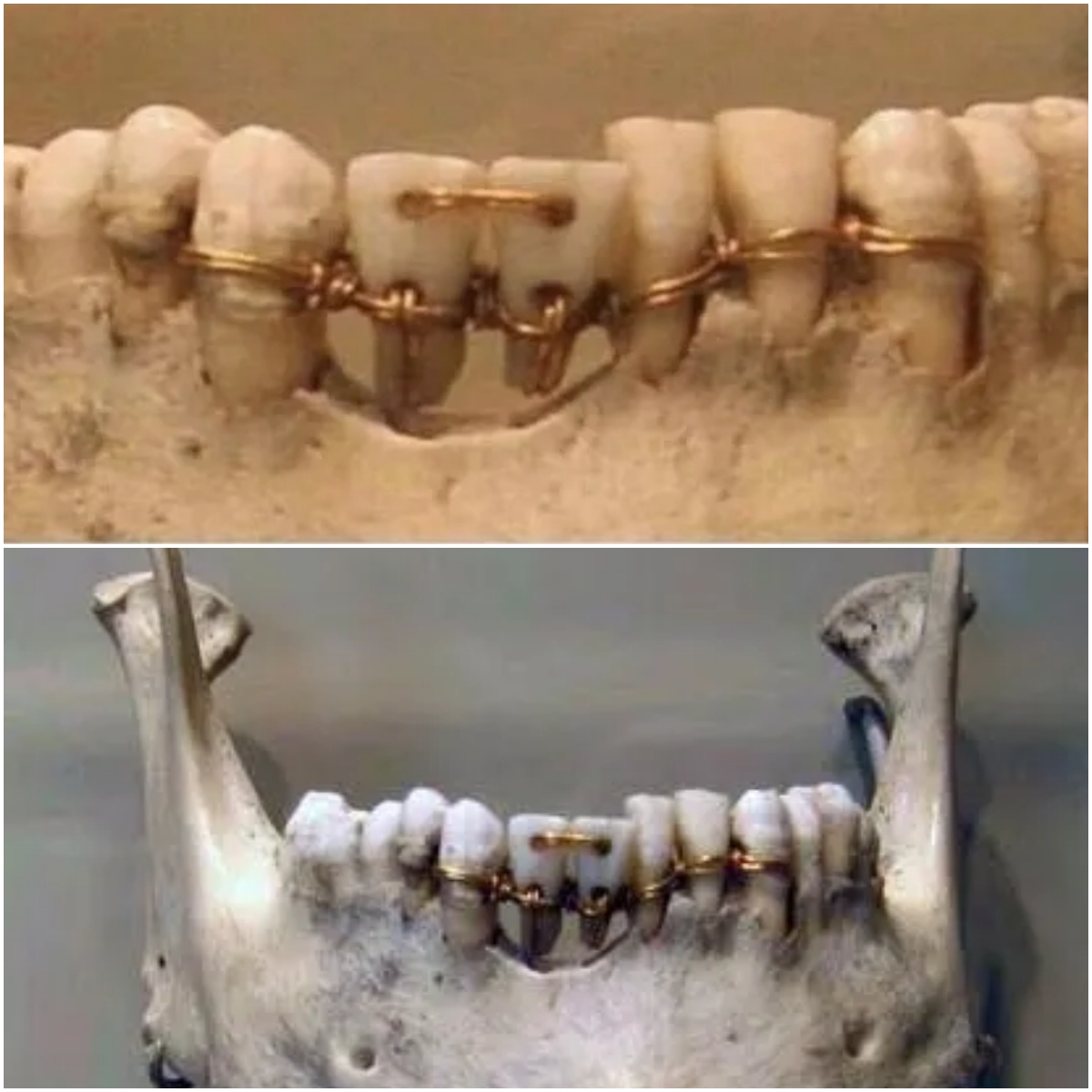

Removal of internal organs: Initially, the brain was carefully removed through the nostrils using a special hook, reflecting the belief that it was not essential for the afterlife. Meanwhile, other internal organs likely to disintegrate quickly were removed. The heart, considered the essence of life and being, was often left within the body as it was believed to be essential to the rebirth of the deceased in the afterlife.

Natron dehydration: The body was then dehydrated using natron, a natural salt that served as both a preservative and a drying agent. This step was crucial to prevent decomposition and prepare the body for wrapping.

Wrapping: The final step involved wrapping the body in over a hundred meters of linen. Linen was often treated with rubber, which acted as an adhesive to seal the wrappers and protect the body. Variations according to social class

Rich and elite: For the wealthy, the mummification process was elaborate. The brain was removed through the nasal passages with a crooked iron tool. The abdominal cavity was cleaned with palm wine, filled with luxurious spices such as myrrh and cassia, and then sewn up. After the 70-day natron treatment, the body was washed, wrapped in fine linen, and covered with gum. This meticulous care ensured the preservation of the individual’s appearance and status even in death.

Middle class: A less expensive method involved injecting cedar oil into the abdomen, which dissolved the internal organs. After the natron treatment, the oil was extracted, leaving the body essentially a figure of skin and bones. This process was less expensive but still preserved the body for the afterlife.

Poor: The most economical method used for the lower class involved a simple oil enema to cleanse the intestines, followed by natron treatment. This method was simple and much less laborious, reflecting the economic limitations of the lower classes.

The decline and legacy of the art of mummification

In the 4th century AD. C., when Rome dominated Egypt and Christianity spread, the art of mummification faded. However, the practice has provided a rich historical perspective on Egyptian culture and traditions. Mummification is still performed in various forms around the world, from rituals in Papua New Guinea to modern embalming in Western funeral homes and preservation techniques in medical and educational settings, demonstrating the timeless human fascination with preserving the dead.

But that doesn’t mean body preservation is dead. Mummification was not limited to Egypt, and in some ways the tradition has also transcended time. The people of Papua New Guinea still mummify their deceased. Additionally, Western funeral homes often embalm corpses to slow decomposition and allow time for ceremonies to take place. Even anatomical laboratories are known to use techniques that preserve bodies for medical and educational purposes.

The ancient Egyptians’ mastery of mummification has left a lasting legacy that goes beyond historical curiosity and contributes to modern scientific and cultural understanding. By preserving their dead, the Egyptians not only ensured the survival of their loved ones in the afterlife, but also the enduring legacy of their civilization in human history. As we decipher more of their methods and meanings, we not only gain insights into their world, but also a deeper appreciation of our own mortal existence and the ways we choose to remember and honor our dead.