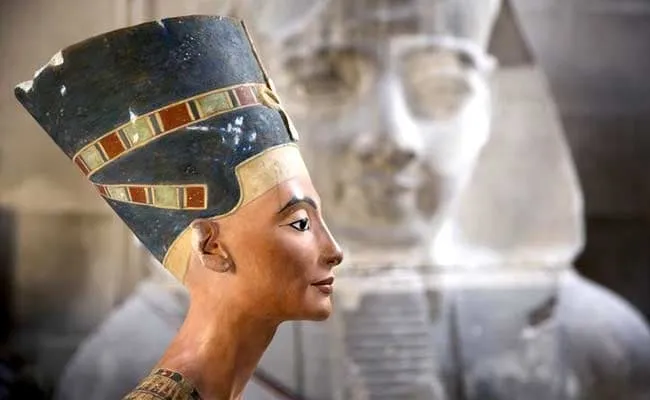

Queen Nefertiti’s mummy may have been found, says leading archaeologist

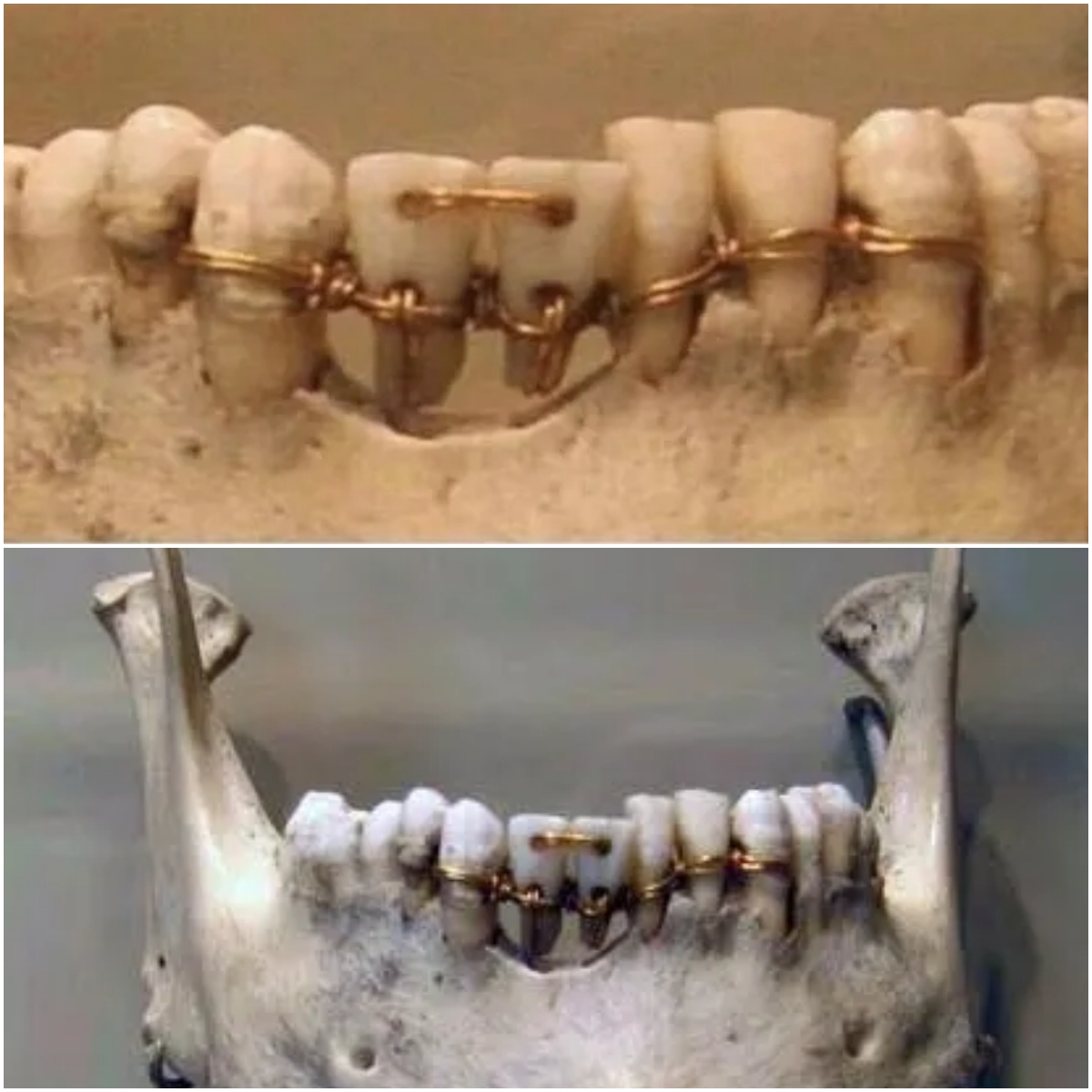

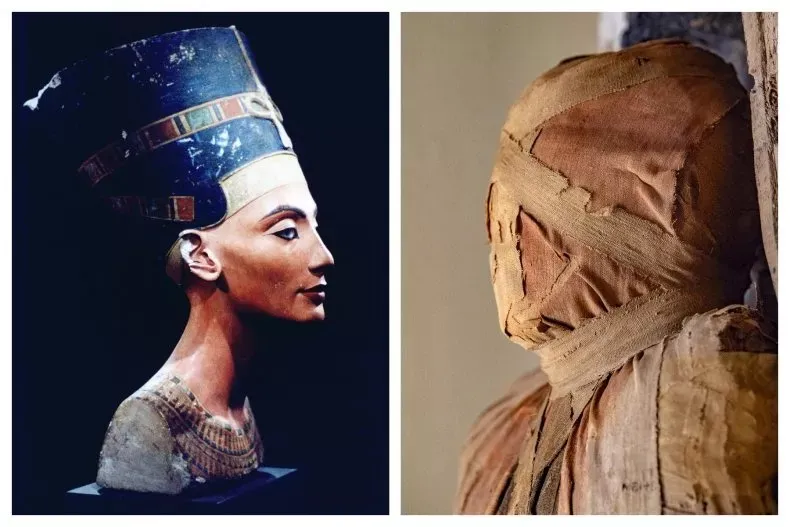

Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass examines mummy KV21B in a storage room at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo before performing a DNA sample and CT scan to determine its family tree. This mummy was discovered with another, KV21A, in a tomb discovered in 1817 in the Valley of the Kings. Both mummies may be queens of the 18th dynasty. Hawass and other Egyptian archaeologists consider KV21B to be a candidate for the body of Nefertiti.

Leading Egyptologist Zahi Hawass recently said he is certain a mummy he is currently studying will turn out to be that of Queen Nefertiti.

Hawass, who has been studying Egyptian history and excavating ancient tombs for decades, and was previously Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs in Egypt, is currently preparing an exhibition called ‘Daughters of the Nile’, focusing on women in Pharaonic Egypt.

“I am sure that I will reveal the mummy of Nefertiti in one or two months,” Hawass told Spanish newspaper El Independiente in an interview.

Nefertiti, whose full name was Neferneferuaten Nefertiti, lived from approximately 1370 to 1330 BC. Married to Pharaoh Akhenaten, she was queen of Ancient Egypt during a period of great wealth and was the mother of Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut.

Some believe that after her husband’s death, Nefertiti ruled as queen, though others disagree. Hawass is one such believer.

“I am still looking for two things: [Nefertiti’s] tomb and her body,” Hawass said. “I truly believe that Nefertiti ruled Egypt for three years after Akhenaten’s death under the name Smenkhkare.”

While mummified remains of multiple pharaohs and important figures of ancient Egypt have been discovered, Nefertiti has yet to be identified.

“We already have DNA from mummies of the 18th Dynasty, from Akhenaten to Amenhotep II or III, and there are two unnamed mummies labelled KV21a and b,” he said. “In October we will be able to announce the discovery of the mummy of Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s wife, and her mother, Nefertiti. Also in tomb KV35 is the mummy of a 10-year-old boy. If that boy is Tutankhamun’s brother and Akhenaten’s son, the problem posed by Nefertiti will be solved.”

“I am sure I will reveal which of the two anonymous mummies could be Nefertiti,” Hawass added.

The ancient Egyptians mummified the bodies of their most important dead in a lengthy process that lasted up to 70 days, according to the Smithsonian Museum.

First, all internal organs except the heart were removed to slow their decomposition, using instruments with special hooks to extract the brain in pieces from the nose. The organs were placed in another container and buried with the body. After this step, the body was completely dehydrated using a special salt called natron, which was coated on and inside the body. The bodies were then wrapped in linen and placed in a tomb.

Despite being a source of great intrigue and research for over a century, it is believed that there are still a large number of mummies and treasures left undiscovered from Ancient Egypt.

“We have only found 30 percent of what is underground. A few days ago, a mission found tombs inside several houses in Alexandria,” Hawass said. “Modern Egypt is built on ancient Egypt. And that is why the heritage that remains hidden is immense.”

However, some of Ancient Egypt’s undiscovered treasures may be lost before they can be studied, Hawass said.

“I sincerely believe that [the main threat to the preservation of Egyptian heritage] is climate change,” he said. “The question is: How can the tombs in the Valley of the Kings be protected? If we leave the situation as it is now, within a century all the tombs will have completely disappeared. We need to equip ourselves with a protection plan especially for tombs and temples. Once a year I usually take a photograph of the walls of the Kom Ombo temple and every time I go back, 5 percent of the reliefs have faded. We must work to control climate change.”

Hawass says the only way to preserve Egypt’s history is to close and open the tombs every year, and have a reservation process to enter the tombs.

“There must be a centre to monitor climate change and tourism,” he said. “Tourism is the enemy of archaeology, but we must find a middle ground between the need for tourism for the economy and the preservation of Egyptian monuments. This is extremely important.”