Pyramid Construction: Aliens Not the Answer

Greek historian Herodotus wrote that it took 100,000 men and 20 years to build the Great Pyramid of Giza, but how exactly did they do it?

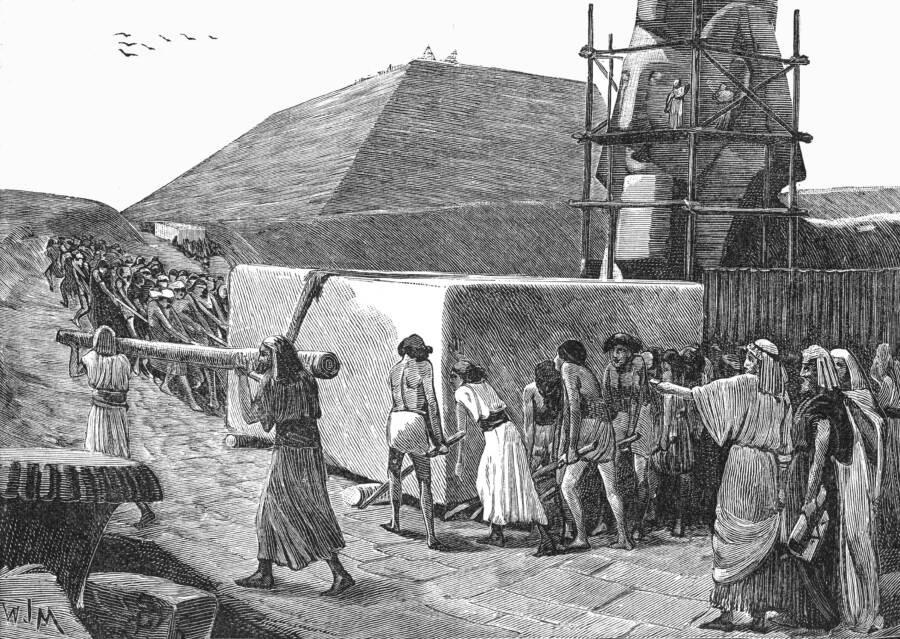

By Luan / Alamy Stock Photo An illustration depicting the construction process of the Egyptian pyramids.

Built 4,500 years ago during Egypt’s Old Kingdom, the Pyramids of Giza are more than just elaborate tombs: They are also one of historians’ best sources of information about how the ancient Egyptians lived, as their walls are covered with illustrations of agricultural practices, city life and religious ceremonies. But on one topic, they are curiously silent: they offer no insight into how the pyramids were built.

It is a mystery that has plagued historians for thousands of years, leading the wildest speculators into the murky territory of extraterrestrial intervention or other fringe theories. However, the work of several archaeologists in recent years has dramatically changed the landscape of Egyptian studies.

After millennia of debate, the mystery may finally be over.

The mystery of how the pyramids were built

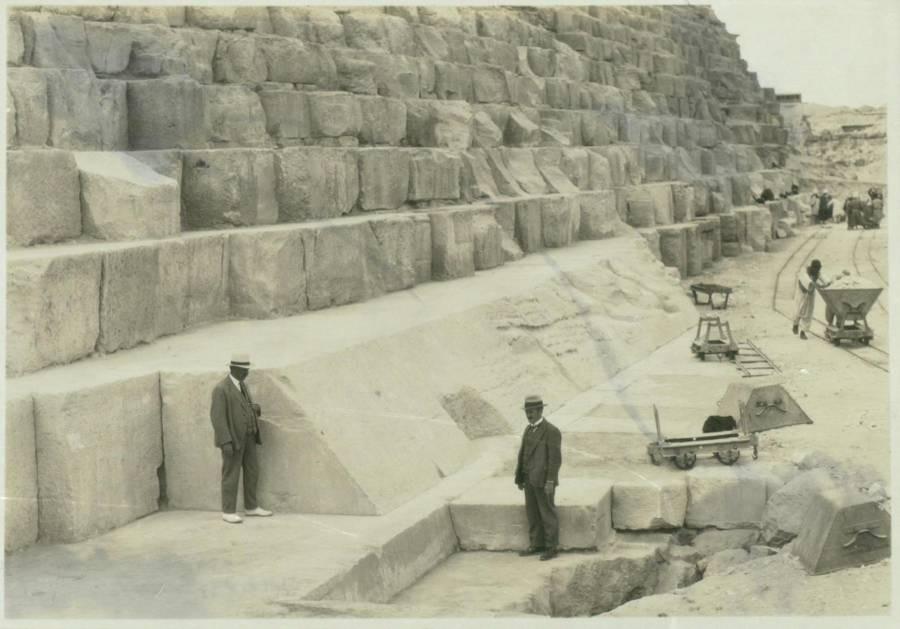

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library/Flickr The mystery of how the pyramids were built has puzzled historians for centuries. Here, a team examines the masonry in 1925.

Why have the pyramids perplexed generations of archaeologists? For one thing, they are an astonishing feat of engineering made particularly impressive by what we know their architects didn’t have. Even by modern standards, the Egyptian pyramids are astonishingly complex and structurally sound. When you factor in the fact that the ancient Egyptians lacked a variety of tools that would have made building such amazing structures easier, it’s easy to see why their construction has been the subject of so many different theories.

For example, the Egyptians had not yet discovered the wheel, so it would have been difficult to transport huge stones (some of them weighing up to 90 tons) from one place to another. They had also not yet invented the pulley, a device that would have made it much easier to lift large stones and move them into place. They did not even have iron tools to chisel and shape the blocks.

And yet, Cheops, the largest of the pyramids at Giza, is 481 feet of massive, impressive masonry. Its construction began around 2560 B.C.

Khufu and its neighbouring tombs have survived 4,500 years of war and desert storms, and are made from plans and measurements accurate to a fraction of an inch. There’s a reason they’re considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and why they’re the only ones still standing.

The heated debate over how the pyramids were built

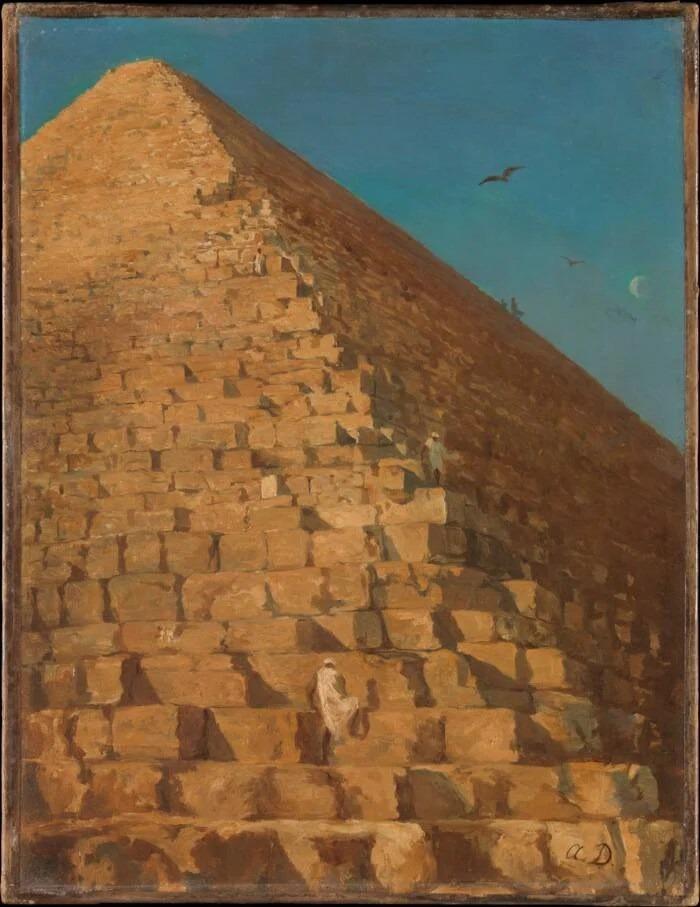

Metropolitan Museum of Art/Public DomainA painting from around 1830 by Adrien Dauzats depicting the stacking of stones at the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Many historians are convinced that the building materials for the Giza pyramids came from nearly 500 miles away.

To solve the problem of how such large stones got so far, some researchers have hypothesized that the Egyptians rolled their stones across the desert.

Although they did not have the wheel as we know it today, they could have used cylindrical tree trunks laid side by side along the ground. If they raised their blocks on those tree trunks, it is quite possible that they would have rolled them across the desert.

This theory largely explains how the smaller limestone blocks from the pyramids could have arrived at Giza, but it’s hard to believe it works for some of the truly massive stones found in tombs.

Proponents of this theory also have to deal with the fact that there is no evidence that the Egyptians actually did this. As clever as it might have been, there are no depictions of stones, or anything else, rolled in this way in Egyptian art or writings.

Then there is the challenge of how to lift the stones into position in an ever-taller pyramid.

History of Science Images / Alamy Stock Photo A 1759 lithograph by French artist Gouget showing the pyramid building technique described by Herodotus.

Ancient Greek historians born after the pyramids were built believed that the Egyptians built scaffold-like ramps along the faces of tombs and carried stones up them. Some modern theorists have pointed to strange air pockets suggesting that the ramps were actually inside the walls of the pyramids, which is why no trace of them remains on the outer faces.

No conclusive evidence has been found in favor of either of these ideas, but both remain intriguing possibilities.

Surprising new solutions shake up the debate

Amid such mystery, two new revelations about how the pyramids were built have come to light in recent years. The first was the work of a Dutch team that took a second look at Egyptian art depicting workers dragging huge stones on sleds across the desert.

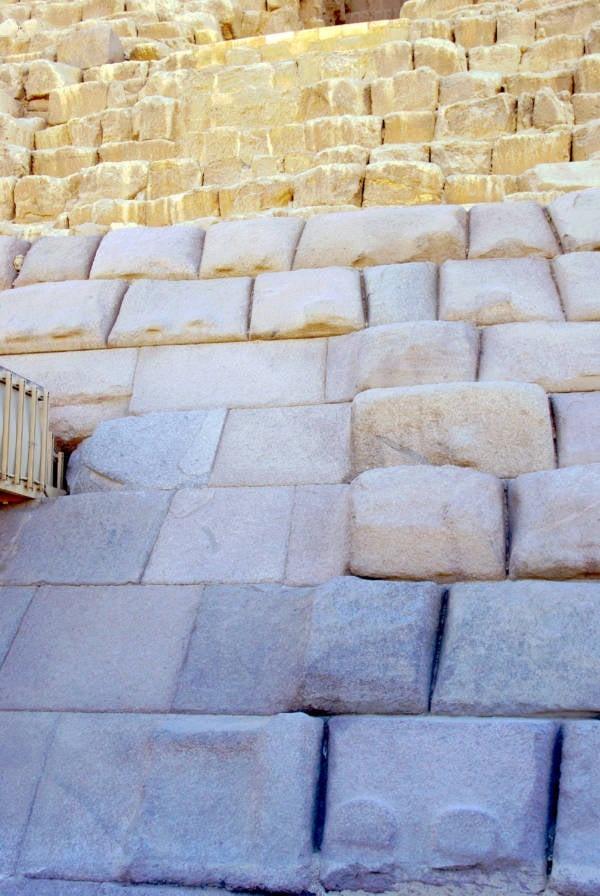

Wikimedia CommonsUnfinished stones at the base of Menkaure.

They realized that the small figure pouring water onto the stone’s path wasn’t simply offering the desert some sort of ceremonial libation: it was wetting the sand because of the principles of fluid mechanics: water helps grains of sand stick together and significantly reduces friction, allowing the ancient Egyptians to more easily move huge blocks of stone across the desert.

The team, which published its findings in the journal Physical Review Letters, built its own replica sleds and tested its theory. The result? The Egyptians may have been able to move larger stones than archaeologists and historians ever thought possible.

But that’s not all. Egypt expert Mark Lehner has proposed another theory that makes the way the pyramids were built a little less mysterious.

Although the pyramids today stand amid miles of dusty desert, they were once surrounded by the floodplains of the Nile River. According to a 2003 article in Harvard Magazine, Lehner hypothesized that if you could look deep beneath the city of Cairo, you would find ancient Egyptian canals that funneled Nile water to the pyramids’ construction site.

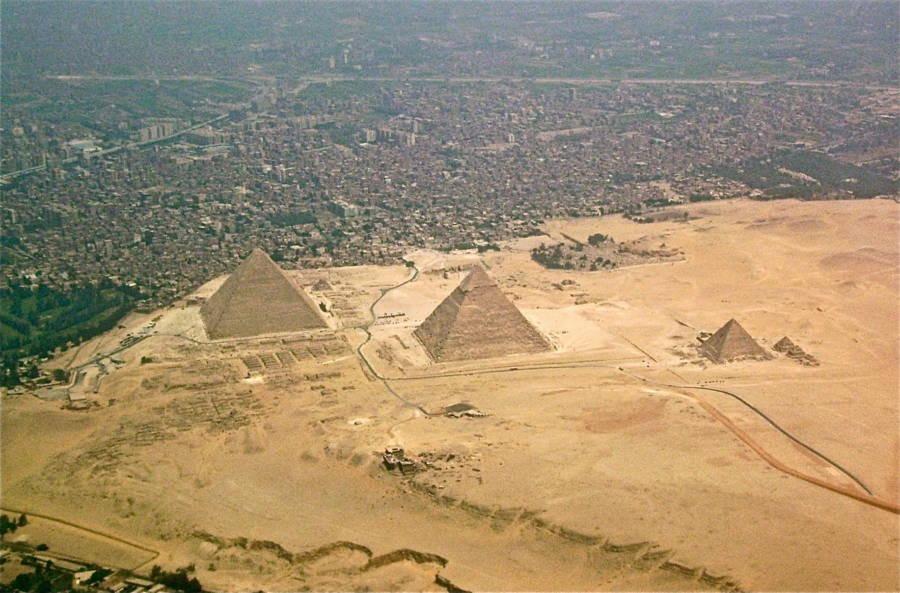

Wikimedia Commons An aerial view of the pyramids of Giza.

In theory, the Egyptians could have loaded these massive stones onto ships and transported them along the river to wherever they were needed. Best of all, Lehner found proof: His excavations revealed an ancient harbor right next to the pyramids, where the stones would have landed.

The icing on the cake is the work of Pierre Tallet, an archaeologist who, in 2013, unearthed the papyrus diary of a man named Merer, who appears to have been a low-level bureaucrat tasked with transporting some of the materials to Giza.

After four years of painstaking translation, Tallet discovered that the ancient chronicler, responsible for the oldest papyrus scroll ever found, described his experiences supervising a team of 40 workers who opened dams to divert Nile water into artificial canals that led directly to the pyramids.

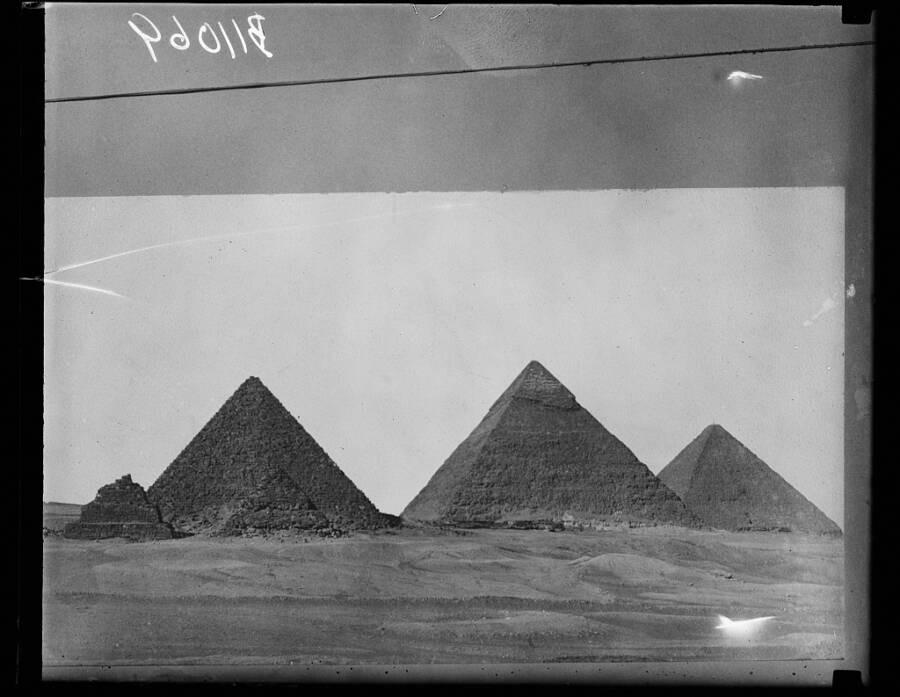

Harris & Ewing Collection/Library of Congress The pyramids of Giza in 1936.

He recorded his journey with several giant limestone blocks from Tura to Giza, and his writings offer the most direct insight ever into how the pyramids were built, putting into place a piece of one of the world’s oldest puzzles.

Another mystery of Ancient Egypt solved

Mark Lehner’s excavations also settled another debate about how the pyramids were built: the question of slave labor. For years, popular culture has imagined the monuments as bloody sites of back-breaking forced labor where thousands perished in involuntary servitude.

Wikimedia Commons The Great Sphinx of Giza watches over the pyramids.

Although the work was dangerous, it is now believed that the men who built the tombs were probably skilled workers who volunteered their time in exchange for excellent rations. The 1999 excavation of what researchers sometimes call the “pyramid city” shed light on the lives of the builders who built their homes in nearby compounds.

The archaeological team unearthed astonishing amounts of animal bones, especially bones from young cows, suggesting that pyramid workers regularly ate prime beef and other prized meats grown on outlying farms.

They found comfortable-looking barracks equipped with the amenities of well-off Egyptians and appearing to house a rotating crew of workers.

Wikimedia Commons A map of the Giza pyramid complex.

They also discovered a significant cemetery of workers who died on the job, yet another reason why researchers now believe the men responsible for building the pyramids were likely skilled workers. The work was dangerous enough without including unskilled people in the mix.

Although they were handsomely rewarded and most likely worked voluntarily (in short, not as slaves), how they felt about the risks they took remains a mystery. Were they proud to serve the pharaohs and build their vehicles for the afterlife? Or was their work a social obligation, a kind of conscription that mixed danger and duty?

We can only hope that future excavations will continue to provide new and interesting answers.

Did you enjoy this breakdown of how the pyramids were built? Check out these other unsolved ancient mysteries. Then, read about these incredible pyramids not found in Egypt.