WATCH (VIDEO): Ancestral cannibalism: Evidence found among humanity’s earliest relatives from 1.45 million years ago

Researchers at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History have unearthed a chilling discovery: the oldest definitive evidence of human relatives killing and likely eating each other. The discovery comes in the form of a 1.45-million-year-old shinbone from a relative of Homo sapiens, found in northern Kenya.

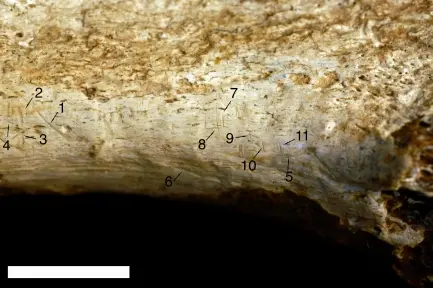

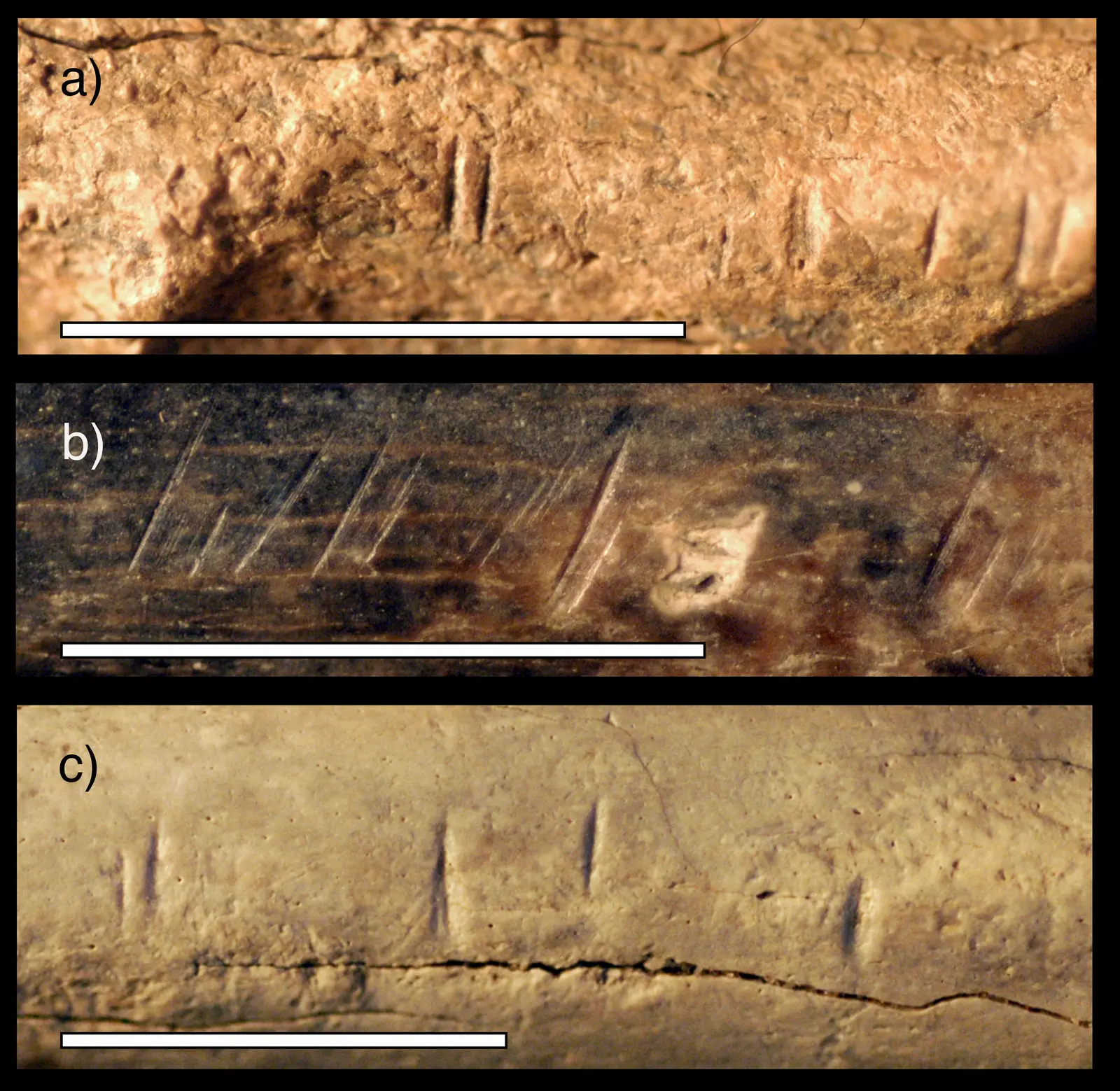

Cut marks on a 1.45-million-year-old shinbone suggest stone tools were used to cut open the leg and harvest its meat.

Analysis of the fossilized tibia, or shinbone, revealed nine distinct cut marks consistent with damage inflicted by stone tools. These marks were located where the calf muscle would have attached to the bone, suggesting a deliberate attempt to extract meat for consumption. Furthermore, all of the cuts were oriented in the same direction, implying that they were made with a single stone tool in rapid succession.

Three fossilized animal bones from the same region and time horizon as the recently analyzed tibia show similar butchery marks.

While the cut marks point toward cannibalism, the exact nature of the act remains unclear. The fossilized bone cannot be definitively assigned to a specific hominin species, a group that includes modern and extinct humans as well as our close relatives. This ambiguity leaves open the possibility that one hominin species consumed another related but distinct species.

This newly discovered shin bone is the strongest candidate for being the first confirmed case of hominins eating each other. However, a roughly 2-million-year-old Homo habilis or Australopithecus skull from South Africa has also been discussed as a potential example of early cannibalism. Recent studies of the skull marks suggest they may be due to natural processes rather than butchery.

A 3D model of the incisions on the tibia helped scientists identify them as cut marks made with stone tools.

The study’s lead author, Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner, stumbled upon this discovery while examining bones at the Nairobi National Museum in Kenya. She was initially looking for predator bite marks on fossilized bones, but instead noticed these distinctive cut marks.

Pobiner believes the cut marks likely indicate the hominid’s leg was butchered for food, not as part of a ritual. This conclusion is based on the location and orientation of the cuts, which align with practices observed in processing animal bones for consumption.

The fossilized tibia has nine cut marks inflicted with stone tools where a calf muscle would have attached to the bone.

Researchers also identified two bite marks on the bone, likely left by a large cat, possibly a sabre-toothed cat native to the region at the time. The presence of these bite marks next to the cut marks makes it difficult to determine the sequence of events. Hominids could have scavenged the remains after a big cat was killed, or they could have seized the carcass after a big cat was forced to abandon its prey.

Pobiner stresses the importance of revisiting museum collections. This discovery highlights the potential for groundbreaking revelations by reexamining existing fossils with new perspectives and techniques.

This study underscores the value of combing museum collections with advanced analytical techniques, which could uncover new insights from well-studied specimens. Pobiner hopes that future research will shed light on similar finds, such as the debated markings on a South African skull, further enriching our understanding of early hominin behaviour and ecology.